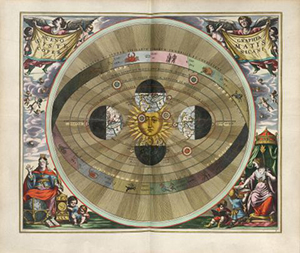

During the 2006-2007 season, Magnificat presented four programs, two of which were repeated on tour. In addition to our usual subscription series concerts in Palo Alto, Berkeley, and San Francisco, Magnificat appeared on the Tropical Baroque Festival in Miami and as part of the Society for Seventeenth Century Music conference at Notre Dame University in South Bend, Indiana. The image used on Magnificat’s brochure and website for the season, both designed by creative director Nika Korniyenko, was from Harmonia Macrocosmica by Andreas Cellarius published in 1660.

During the 2006-2007 season, Magnificat presented four programs, two of which were repeated on tour. In addition to our usual subscription series concerts in Palo Alto, Berkeley, and San Francisco, Magnificat appeared on the Tropical Baroque Festival in Miami and as part of the Society for Seventeenth Century Music conference at Notre Dame University in South Bend, Indiana. The image used on Magnificat’s brochure and website for the season, both designed by creative director Nika Korniyenko, was from Harmonia Macrocosmica by Andreas Cellarius published in 1660.

The season began in October with a program of music that Marc-Antoine Charpentier wrote while he was music master of the Saint-Chapelle. Founded in the 13th Century, the Sainte-Chapelle was situated in the heart of a walled enclosure of what was formerly the palace of the king and, during Charpentier’s tenure, the Parlement. The reconvening of the Parlement, which took place annually on November 12, the day after the Feats of St. Martin, was commemorated by the celebration of a grand ceremonial mass, called the Messe Rouge because of the magistrates scarlet vestments. The two works on Magnificat’s program were written for performance at the “Red Mass”, the Motet pour une longue offrande in 1698 and Judicium Salomonis (The Judgement of Solomon) in 1702.

In her review for the San Francisco Classical Voice, Michelle Dulak Thomson praised Magnificat as “and ensemble that can do it all,” observing “[o]ne of the recurring joys of hearing Magnificat is the ease with which the ensemble slips into the stylistic garb of each program. It takes an uncommonly disciplined musical sensibility to range as widely over this bewildering century as these musicians do — and yet they always seem right at home. On Saturday night, the rhetorical tone was just right for Charpentier: poised and serene, perceptibly stylized and yet sincere, unfailingly elegant — but also, rejoicing unabashedly in the richness of the harmony. The performance-practice niceties — the easily swung notes inegales, the lovingly dwelt-upon cadential appoggiaturas, the (to my ears) impeccable French Latin — all seemed as natural as breathing.”

In December, Magnificat performed a program model on one that had been part of our 1998 season featuring the music of Dietrich Buxtehude. The program included seven Advent cantatas whose central themes involve the expectation of the arrival of the divine beloved. The texts include mystical devotional poems, Lutheran chorales, and scripture and the affective range of

the cantatas reflect the emotional richness of the season, from joyous anticipation to somber self-examination and spiritual preparation. The program also included two ensemble sonatas. Buxtehude’s sonatas owe more to the tradition of improvisatory virtuoso music of mid century Germany than to the Corelli trio sonatas that had become the model across Europe by the end of the century. It is possible that some of the music on the program may have been incorporated into Buxtehude’s famous Abendmusik productions, though it is just as likely that it was intended for devotional services in court or private situations.

Writing in the San Francisco Classical Voice, Joseph Sargent wrote “Buxtehude — more familiar to audiences for his organ music — has a distinguished output of sacred vocal music that reveals a composer of great invention who could deploy a stunning variety of textures and styles over the span of just a few minutes of music. Magnificat proved up to the task of negotiating these shifts, delivering a sparkling performance that further established their Bay Area reputation as a leading interpreter of 17th century repertory.”

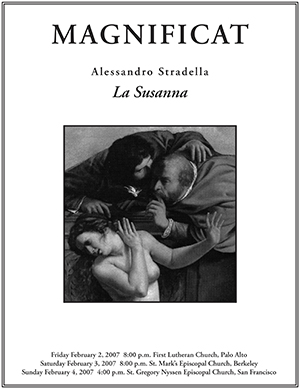

In February 2007, Magnificat presented Alessandro Stradella’s oratorio La Susanna. One of at least 86 oratorios composed during his tragically shortened life, La Susanna was commissioned by the Francesco, Duke of Modena. Its text, in two Parts as was usual, was written by the Modenese poet Giovanni Battista Giardini, who was also secretary to Francesco, and he based his libretto on the biblical account of Susanna given in chapter 13 of the Book of Daniel.

After three performances on our series in the Bay Area, Magnificat travelled to Miami to perform Susanna at the Tropical Baroque Festival. In his review for the Miami Herald, Alan Becker praised Laura Heimes, who sang the title role, as “balm to the ears. Her tones were perfectly floated over the ensemble, and her willingness to sing softly made her a Susanna of beauty indeed.”

For the final program of the season, Magnificat returned to the music of Chiara Margarita Cozzolani, with music for vespers that was repeated at the conference of the Society for Seventeenth Century Music at Notre Dame University. Kathryn Miller observed in the SFCV review“Cozzolani’s distinctive style focuses on contrasts. Long, spun-out homophonic lines turn suddenly to quick moving polyphony, out of which a soloist will emerge, only to be drawn back into the ensemble. These musical contrasts are also paired with dramatic shifts, and the women of Magnificat deftly crafted each moment, infusing phrases with freshness and spontaneity. Each new motive or dynamic bloomed and grew.”

The performance at Notre Dame was an important one for Magnificat artistic director Warren Stewart. “Performing at the 17th Century music conference was a special thrill for me,” noted Stewart. “It was a privilege to perform for a select audience of musicologists, many of whom had devoted their lives to researching the music of women and specifically nuns in the 17th century. A high point!”

During the course of the season, artistic director Warren Stewart led ensembles that included Elizabeth Anker, Peter Becker, Louise Carslake, Christopher Conley, Steve Cresswell, Rob Diggins, John Dornenburg, Kristen Dubenion Smith, Jolianne von Einem, Paul Elliott, Jennifer Ellis Kampani, Andrea Fullington, Katherine Heater, Laura Heimes, Dan Hutchings, Suzanne Jubenville, Jennifer Paulino, Hanneke van Proosdij, Byron Rakitzis, Deboah Rentz-Moore, David Tayler, Catherine Webster, and David Wilson.

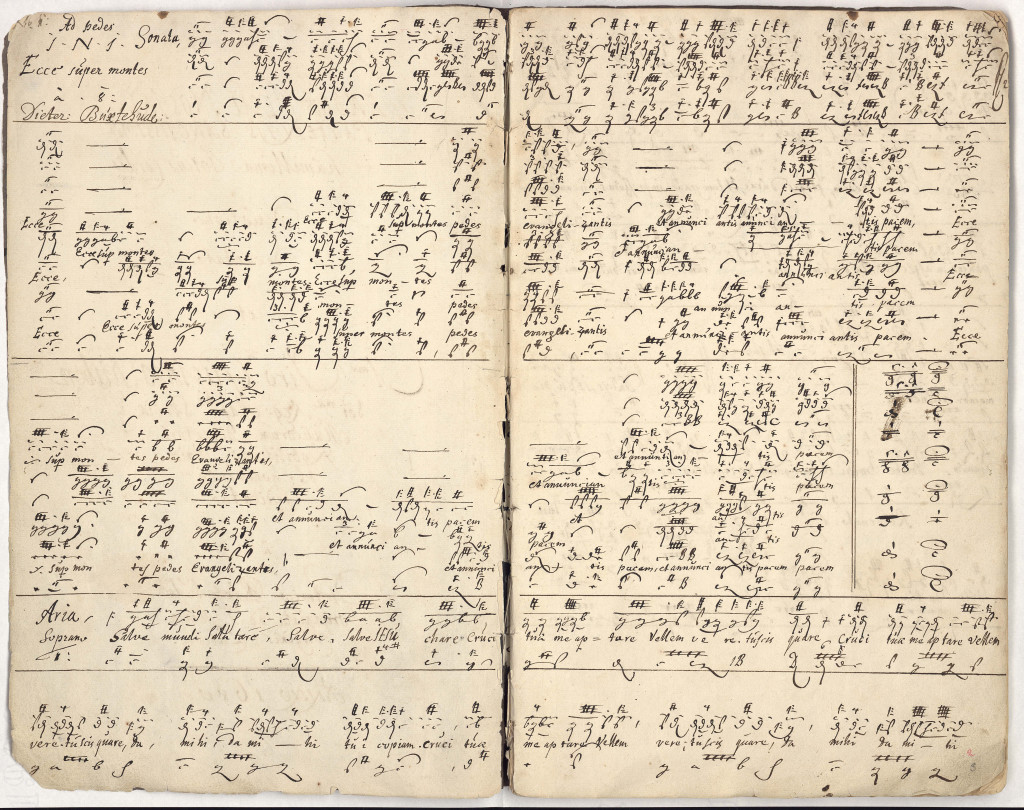

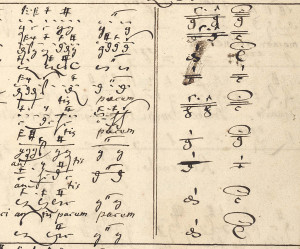

Musicians often refer to the ‘road map’ for a performance of music with repeats, da capos or added codas – music that, explicitly or not, offers the performer options in determining the structure of the work. “How many times do we repeat the A section when we make the repeat?” Rehearsal decisions often lead to cryptic notations of letters and numbers in the margins of parts and scores. Ad Pedes, the first cantata in Buxtehude’s cycle Membra Jesu Nostri presents options for several ‘road maps’ that stem from the circumstances of its transmission.

Musicians often refer to the ‘road map’ for a performance of music with repeats, da capos or added codas – music that, explicitly or not, offers the performer options in determining the structure of the work. “How many times do we repeat the A section when we make the repeat?” Rehearsal decisions often lead to cryptic notations of letters and numbers in the margins of parts and scores. Ad Pedes, the first cantata in Buxtehude’s cycle Membra Jesu Nostri presents options for several ‘road maps’ that stem from the circumstances of its transmission.