The Road Map for Ad Pedes from Membra Jesu Nostri

Musicians often refer to the ‘road map’ for a performance of music with repeats, da capos or added codas – music that, explicitly or not, offers the performer options in determining the structure of the work. “How many times do we repeat the A section when we make the repeat?” Rehearsal decisions often lead to cryptic notations of letters and numbers in the margins of parts and scores. Ad Pedes, the first cantata in Buxtehude’s cycle Membra Jesu Nostri presents options for several ‘road maps’ that stem from the circumstances of its transmission.

Musicians often refer to the ‘road map’ for a performance of music with repeats, da capos or added codas – music that, explicitly or not, offers the performer options in determining the structure of the work. “How many times do we repeat the A section when we make the repeat?” Rehearsal decisions often lead to cryptic notations of letters and numbers in the margins of parts and scores. Ad Pedes, the first cantata in Buxtehude’s cycle Membra Jesu Nostri presents options for several ‘road maps’ that stem from the circumstances of its transmission.

Buxtehude dedicated Membra Jesu Nostri to the Swedish court organist and Kapellmeister Gustav Düben and the composer’s autograph manuscript, in tablature notation, survives at the music library of the University of Uppsala in the magisterial Düben Collection. German organ tablature notation is one of a variety of shorthand notations used in Northern Europe during the Renaissance and Baroque periods. Lacking familiar staves, noteheads and key signatures, tablature notations uses script letters for pitches and flags for duration.

A set of parts for each of the cantatas, copied from the tablature by Düben presumably for his performances at the Swedish Court, are also preserved at Uppsala. Correlating the parts with the tablature provides insight into performance practice issues and the circumstances under which the individual cantatas may have been performed and in n the case of the opening cantata it also presents a ‘road map’ puzzle that has been solved in a variety of ways by editors and performers.

The underlying structure of the cantata cycle and its sevenfold meditation on the body of the Christ, is the medieval poem Salve mundi salutare, now thought to be by Arnulf of Louvain (c. 1200–1250). Buxtehude pairs strophes from the seven sections of Arnulf’s poem with scriptural texts using a compositional structure that the musicologist Friedrich Krummacher has referred to as the ‘concerto-aria cantata.’ Each of the cantatas opens with an instrumental sonata, often employing musical motives from the following concerto, which sets a brief scriptural text, in most cases referring to the part of the body to which that section of the poem is addressed. Three strophes from the Arnulf’s poem follow the concerto, scored for one to three voices and continuo, before the concerto is repeated, as indicated by text in the tablature, not unlike the now common indication “dal Segno al Fine.” The symmetrical framing of strophic aria settings of a poetic text with a concerto setting of a prose text, the most common structure for Buxtehude’s vocal works in general, provides the basic shape of each of the seven cantatas, but the composer deviates from this symmetry in subtle ways throughout the cycle. In fact the overall structure is varied in the very first cantata, Ad Pedes, i.e. before it has even been established.

In the tablature, the concerto of Ad Pedes that sets a text from the Old Testament prophet Nahum ends with a half cadence, leaving the listener with a sense of anticipation that is relieved by the subsequent beginning of the first verse. When the concerto is repeated, this half cadence leads surprisingly, but agreeably, to a brilliant coda-like setting of the first strophe for the full ensemble. This tutti setting of the first verse is provided in the tablature after the third verse of Arnulf’s poem (for bass solo with continuo) and the indication to repeat the opening concerto.

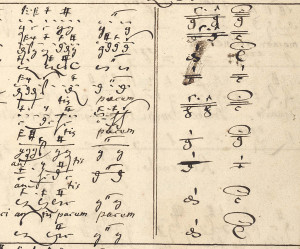

Whatever Buxtehude’s motivation for this unexpected structure, Düben was apparently unconvinced and in an empty space in the tablature next to the half cadence (see image), he inserted a full cadence, suggesting what we would now call a “first and second ending.” In the set of parts, he included the second ending and omitted the tutti setting of the first verse entirely. In this way he ‘regularized’ the structure of the cantata to match that of the other six cantatas, i.e. Sonata-Concerto-Verses-Concerto (though the seventh cantata Ad Faciem also deviates from the structure of the other cantatas by replacing the repeat of the concerto with an extended Amen.)

While Buxtehude’s original intention is unambiguous, Düben’s alterations have lead to several different ‘road maps’ for the cantata. The most recent critical edition, edited by Günther Graulich for Carus Verlag follows the most likely interpretation of Buxtehude’s original indication:

Version 1

Sonata

Concerto (with half cadence)

Verse 1 (Soprano 1)

Verse 2 (Soprano 2)

Verse 3 (Bass)

Concerto (with half cadence)

Verse 1 (Tutti)

I have listened to twelve recordings, a representative but by no means comprehensive list, and this was the solution chosen by five (Cantus Cölln, Netherlands Bach Society, Bach Ensemble Japan, Purcell Quartet and La Petite Bande.) This is also the road map found in the Willibald Gurlitt’s edition of the Buxtehude Complete Works.

A slight modification of this approach is found in two other recordings (Concerto Vocale and Les Voix Baroque, the latter featuring Magnificat’s own Catherine Webster), in which Düben’s full cadence is used for the first time through the concerto, while the half cadence is reserved for the repetition when it leads into the tutti setting of verse 1.

Version 1a

Sonata

Concerto (with full cadence)

Verse 1 (Soprano I)

Verse 2 (Soprano 2)

Verse 3 (Bass)

Concerto (with half cadence)

Verse 1 (Tutti)

The rationale for this modification is obscure as Buxtehude’s half cadence leads equally well to both the solo and tutti settings of the first verse offering no compelling reason for using Düben’s full cadence in a performance following the composer’s intentions in other respects. It does provide some variety of course and makes the half cadence and the tutti setting of verse 1 perhaps more surprising.

A possible alternate reading of the tutti setting of the first verse would be to interpret it as an ‘alternative’ to the solo setting of verse. There is nothing in the tablature to suggest that this was Buxtehude’s intention other than the fact that he provides two settings of the same text. This scheme requires Düben’s full cadence for the repeat of the concerto, as it now concludes the entire cantata.

Version 2

Sonata

Concerto (with half cadence)

Verse 1 (Tutti)

Verse 2(Soprano 2)

Verse 3 (Bass)

Concerto (with full cadence)

This is the solution adopted by Dietrich Killan, editor of the Merseburger edition. I found only one recording that followed this scheme (The Sixteen). While it preserves the symmetry of the textual structure, it is somewhat inconsistent in utilizing Düben’s full cadence, which he seems to have included specifically to make the exclusion of the tutti setting of Verse 1 possible. It also creates an awkward transition from the quite glorious tutti setting of verse one to the more intimate setting for verse 2 for soprano and continuo.

A more convoluted, but nevertheless popular variation of this approach, found in at least four recordings (Sonatori della Gioiosa Marca, Concerto Vocale, La Venexiana, and the Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra), inserts the tutti setting of verse 1 between the concerto (with half cadence of course) and the solo setting of verse 1 and uses Düben’s full cadence in the repeat of the Concerto.

Version 2a

Sonata

Concerto (with half cadence)

Verse 1 (Tutti)

Verse 1 (Soprano 1)

Verse 2 (Soprano 2)

Verse 3 (Bass)

Concerto (with full cadence)

This approach would appear to abandon any attempt to follow the intentions of either Buxtehude or Düben. It also shares the awkward transition from Tutti to solo found in Version 2 – in this case with the same text.

Curiously the one approach that I have thus far found in no edition nor recording is the one actually indicated by Düben:

Version 3

Sonata

Concerto (with half cadence)

Verse 1 (Soprano I)

Verse 2 (Soprano 2)

Verse 3 (Bass)

Concerto (with full cadence)

While it would be a pity to miss the exciting tutti setting of the first verse entirely, this version would at least have the benefit of a basis in the original source, and would appear to have served for at least some contemporaneous performances.

Foregoing our natural tendency to opt for novelty, in our upcoming concerts Magnificat will perform Ad Pedes in Version 1 as we did in previous performances in 1996 and 2003.