I have often said that Marc-Antoine Charpentier never wrote a bad note and with every new work we perform I am amazed anew by the sheer perfection of his technique, his facility in an astonishing range of genres, the subtlety with which he depicts emotion, and his extraordinarily varied harmonic palette. As we prepare for our performances of his delightful Messe de Minuit and the Dialogus inter Angelos et Pastores next month, it seems a good time to look back on Magnificat’s love affair with this most magnificent genius of the French Baroque.

I have often said that Marc-Antoine Charpentier never wrote a bad note and with every new work we perform I am amazed anew by the sheer perfection of his technique, his facility in an astonishing range of genres, the subtlety with which he depicts emotion, and his extraordinarily varied harmonic palette. As we prepare for our performances of his delightful Messe de Minuit and the Dialogus inter Angelos et Pastores next month, it seems a good time to look back on Magnificat’s love affair with this most magnificent genius of the French Baroque.

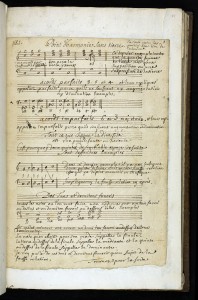

When Magnificat began presenting an annual concert series in 1992, the Charpentier revival was still at a relatively early stage. Though he had been “re-discovered” by the French musicologist Claude Crussard over a half century before and championed heroically in the intervening decades by H. Wiley Hitchcock, there were still relatively few recordings and even fewer modern editions of his works at the time. Since then, a tremendous amount of research has been published by Catherine Cessac, Patricia Ranum, John Powell, and many others, and the composer’s complete manuscripts have been re-printed in facsimile, all of which has allowed a much deeper understanding of Charpentier’s life and art.

Magnificat has dedicated entire programs to Charpentier’s music in twelve of our nineteen seasons, more than any other composer (Schütz and Monteverdi are tied for second place.) Along the way, we have explored many aspects of this prolific and multi-faceted master’s work: the charming divertissements and pastorales composed for the Hotel de Guise, the farsical intermedes written for the stage works of Moliere, Corneille and others, the intimate petits motets for the “Dauphin’s Music” and the sublime histoires sacreés from his time at the Jesuit Church of St. Louis and later at the Sainte-Chapelle. It has truly been a privilege to offer our audiences the opportunity to hear so much of Charpentier’s music.

Magnificat’s first season (1992-93) concluded with a program that showcased both sacred and secular music by Charpentier. The first half of the program included three sacred works representing three different genres: the psalm Super flumina babilonis, the oratorio Le Reniement de St. Pierre and the five part motet Oculi omnium. After intermission it was time for something completely different – a series of comic intermedes written for Moliere’s plays. The highlight of these quite silly vignettes was surely the hilarious “doctors scene” from Le Malade Imaginaire, which included some extemporaneous diagnosis by real-life doctor Gerald Gaul and a fair amount of champagne splattered across the stage.

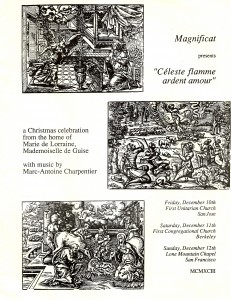

Program from Magnificat's December 1993 concerts - literally cut and paste (with scissors and tape)

Somewhat less raucous was the program for the Christmas concerts in our second season. Charpentier’s Pastorale sur la naissance de notre Seigneur, was performed at the Hotel de Guise, with some variations, on three successive Christmases during the 1680s. Magnificat’s program drew from each of the three versions and integrated some of the infectiously charming noëls (some of which will appear again in this season’s Christmas concerts) in the mix. One of Magnificat’s most beloved programs, we have revived it twice: in 1997 on the San Francisco Early Music Society concert series and on our own series in 2005.

Noëls would not only be included in many of Magnificat’s subsequent Charpentier programs but they also contributed to an interest in voix de villes (or vau de villes), the source for the tunes of many noëls, that featured prominently in two opera parodies presented by Magnificat in 1996 and 1998.

Charpentier was featured again in Magnificat’s 5th season (1996-97) with performances of La Descente d’Orphée aux Enfers, composed in 1686 for one of the musical evenings at the Guise establishment. Derived from an earlier cantata on the same subject, this dramatic work, like so many pieces from the 17th century, defies classification, being neither pastoral, nor cantata, nor opera, yet having some characteristics of each. Above all, Charpentier’s setting of the Orpheus myth displays the influence of his formative years in Rome, where he encountered the music of Carrisimi, Luigi Rossi and others.

Beginning with Magnificat’s 9th season (2000-01), Charpentier’s music has been featured almost every year. That season we presented a program that included two dramatic works, also written for the Hotel de Guise: Actéon and Les Arts florissants. Both works fit into the loosely-defined genre of the divertissement, a term used in seventeenth century France to refer to a wide range of musical works, from interludes in comedie-ballets and tragedie-lyriques, as well as entertainments that resembled the English masque. Some divertissements, like Actéon, were short independent operas on mythological subjects. Others, like Les Arts florissants relate more specifically to the pastorale, originally a literary genre that, over the course of the 17th century began to incorporate music and ballet in the manner of opera.

In the 2002-03 season, working together with musicologist John Powell, Magnificat assembled a program of music that Charpentier composed for stage works of Thomas Corneille (Circé, 1675 and La Pierre Philosophale, 1681) and Raymond Poisson (Les Fous Divertissants, 1680.) With these theatrical works – ranging from pastoral airs to lunatic raving, we returned to the entertaining world of the Le Malade Imaginaire. John’s informative program notes for these concerts can be read here.

In the 2003-04 season, Magnificat performed Charpentier’s cycle of seven motets setting the texts of the Magnificat antiphons for the seven days preceding Christmas. In the Roman breviary these seven antiphons each begin with the acclamation “O” and are therefore known as the “O Antiphons” , “The Great Antiphons” or, as Charpentier refers to them in his title “The Seven Os following the Roman.” In accordance with the composer’s instructions, each of the antiphons was paired with one of his instrumental arrangements of noëls. The program also included the Dialogus inter Angles et Pastores, which we will perform again this season.

Two of Charpentier’s oratorios, or histoires sacreés –Filius Prodigus and Sacrificium Abrahæ–were performed in the final concerts of Magnificat’s 2004-05 season and the Nativity Pastorale was revived for the Christmas program in the 05-06 season. The 35 or so works by Charpentier that can be classified as oratorios form a significant if isolated repertoire nearly unique in France, a country that seemed to have little interest in dramatic settings of religious subjects. Like those of Carissimi, Charpentier’s oratorios are non-liturgical, and freely mix scriptural excerpts with dramatic and poetic interpolations.

A program of music from Charpentier’s tenure at Sainte-Chappelle at the end of his life–Oculi Omnium, the Motet pour une longue offrande, and Judicium Salomonis–opened Magnificat’s 15th season (2006-07.) The Sainte-Chapelle was situated in the heart of a walled enclosure of what was formerly the palace of the king and, during Charpentier’s tenure, the Parlement. The reconvening of the Parlement, which took place annually on November 12, the day after the Feats of St. Martin, was commemorated by the celebration of a grand ceremonial mass, called the Messe Rouge (Red Mass) because of the magistrates scarlet vestments.

A program of music from Charpentier’s tenure at Sainte-Chappelle at the end of his life–Oculi Omnium, the Motet pour une longue offrande, and Judicium Salomonis–opened Magnificat’s 15th season (2006-07.) The Sainte-Chapelle was situated in the heart of a walled enclosure of what was formerly the palace of the king and, during Charpentier’s tenure, the Parlement. The reconvening of the Parlement, which took place annually on November 12, the day after the Feats of St. Martin, was commemorated by the celebration of a grand ceremonial mass, called the Messe Rouge (Red Mass) because of the magistrates scarlet vestments.

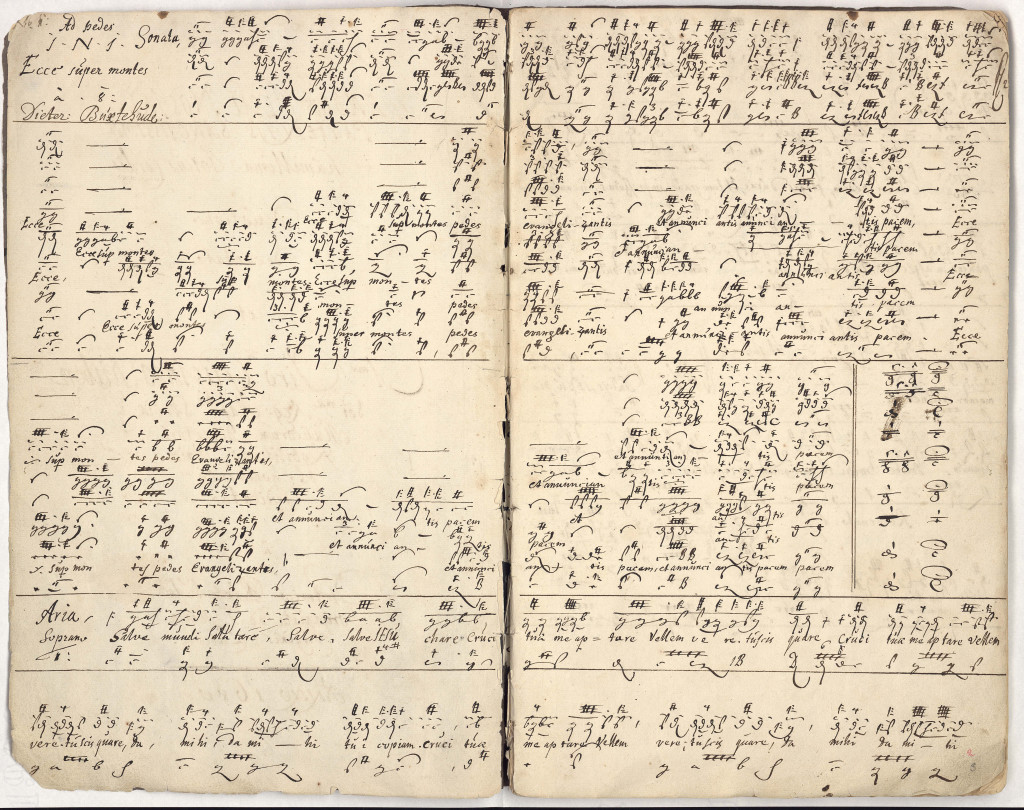

The following season (2007-08,) Magnificat explored another genre of Charpentier’s music – the petits motets – in a program of small chamber works written for the major feasts from Christmas to Purification. Four sacred works follow successively in Charpentier’s manuscripts: Pour la Feste de l’Épiphanie (for the Feast of Epiphany), In Circumcisione Domini (for the Circumcision of our Lord), In Festo Purificationis (for the Feast of Purification), and Pour le Jour de Ste Geneviève (for the Day of Saint Geneviève). Earlier in the notebooks is the Canticum in nativitatem Domini. The similar musical forces required – two sopranos, bass, violins and continuo – imply that they were performed by the same ensemble of singers and instrumentalists. Their placement in Charpentier’s Mélanges autographes suggests that these works were composed during the Christmas season of 1676-1677. Read more here.

Program from October 2008 - graphic design standards have certainly improved!

Most recently, Magnificat a program of Music for the Dauphin – La Couronne de fleurs and Les plaisirs de Versailles – opened Magnificat’s 2008-09 season. From late 1679 until mid-1683, Charpentier composed music for the establishment of the eldest son of Louis XIV and Queen Marie-Thérèse. Both works on the program are examples of the operatic divertissement: a short entertainment that is sung throughout in the manner of an opera, though much shorter than the operas of the time. Read more here. An excerpt from those performances, featuring soprano Laura Heimes can be heard here.

I am very grateful to all those who have supported Magnificat over the years and given us the chance to perform so much of Charpentier’s music. In particular, Magnificat Artistic Advisory Board member John Powell has been very generous in preparing scores, writing program notes and articles, and offering great ideas over the years. Most of all, I am grateful to the splendid musicians who have given their love and talents to Magnificat’s performances of Charpentier’s music. I only wish we could perform each of the programs again!