Charpentier’s Noëls

While I will miss the joy of sharing a full season of terrific music from the early Baroque with my colleagues and with Magnificat’s loyal audience next season, I am very pleased that I will be in California in December to lead Magnificat in a program that it very dear to me. In addition to my personal emotional connection with Charpentier’s music, his character and the circumstances in which he wrote, this particular program represents a fascinating period of discovery for me personally.

While I will miss the joy of sharing a full season of terrific music from the early Baroque with my colleagues and with Magnificat’s loyal audience next season, I am very pleased that I will be in California in December to lead Magnificat in a program that it very dear to me. In addition to my personal emotional connection with Charpentier’s music, his character and the circumstances in which he wrote, this particular program represents a fascinating period of discovery for me personally.

The first music by Charpentier that I had the chance to perform was the Messe de Minuit(Midnight Mass) – a charming work that seamlessly weaves the folk melodies of noëls, already centuries old during the composer’s life with a rigorous contrapuntal ideal. While the Nativity Pastorale does not incorporate noël melodies like the Midnight Mass, there are striking similarities in the poetic imagery of the noëls and their musical character. In Magnificat’s first production of the Nativity Pastorale in 1993, we included several of Charpentier’s instrumental settings of noëls in addition to the Pastorale and I had the chance to learn about these remarkable melodies. I found the noëls especially intriguing because they provided a rare glimpse of the 17th century from a non-aristocratic perspective. Noëls were everyone’s music – nobility and peasants alike shared the joy of these infectious melodies and the often strikingly poignant poetry that these melodies set.

The program notes from Magnificat’s earlier performances of this program note that beginning in the mid-sixteenth century, the words for these simple songs were published in inexpensive, sloppily produced editions called bibles de noelz, and were circulated throughout the provinces by colporteurs or itinerant peddlers and booksellers. Contemporary writers describe these bibles as being found on the hearth in every peasant cottage: greasy, yellowed, and dog-eared. The melodies were pre-existing, anonymous, orally transmitted vaudevilles. Sebastian de Brossard in his music dictionary of 1703 defined noëls as “certain songs in honor of the birth of Jesus Christ set to vaux de villes, or common tunes, that everybody knows.” The melodies were never notated in these popular bibles; it was enough to mention the first few words of the original song, called the timbre, at the beginning of the poem. The best known noël to English audiences Un flambeau set to a timbre that was originally a drinking song Qu’il sont doux, bouteille jolie, attributed variously to Charpentier and Lully.

Although some significant poets contributed to the genre, the poems were usually anonymous, written by schoolteachers, priests, or organists in every town, often in dialect and most probably spontaneously improvised to include the names of friends and neighbors. The texts are often wonderfully exuberant, describing the earthly festivities that accompany the divine birth, including recipes for food to be brought to the party, and a certain amount of practical joking. These noëls increased in popularity throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and made their way into liturgical services, to the displeasure of church authorities. In 1725 the Council de la Province d’Avignon prohibited the singing of noëls in church on the grounds that they “debased the holy mysteries by mixing them with comic things and profane chattering and games.” This disapproval did not stem the popularity of the noëls and bibles de noelz continued to be produced even after the Revolution.

Many of the noël melodies also served for different sentiments at different times of the year – with different words of course. For it was the melody that was ancient – the words were adapted to fit the occasion and indeed, some of the tunes I had first encountered as the equivalent of Christmas carols appear in the slapstick operas parodies that Magnificat performed later in the 90s. No reason to limit a good tune to one season of the year after all!

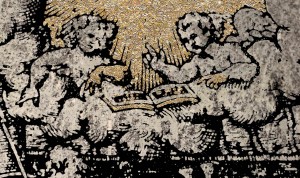

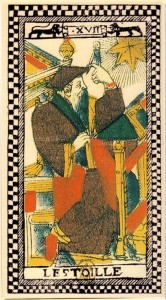

We have used some of the images found in these mass-produced noël collections for earlier productions of the Nativity Pastorale and while for our first production in 1993 the program was assembled (by me) using a photo-copier, scissors, and tape, we now have the benefit of digital editing programs and the talents of our creative director Nika Korniyenko. The images reminded me of the first mass produced playing cards, also a 17th-Century French phenomenon. In both cases, while the wood-cut images are somewhat crude they are nonetheless extremely expressive and even mannerist in their exaggerated gestures and symbolism. The Tarot images have also featured in programs and brochures over the years, for example the “Star” from the Tarot de Paris, published in the early 17th Century, which served as the image for our 2000-2001 brochure. In fact, the gesture on that particular card is similar to the shepherd from the noël woodcut.