Magnificat’s 2011-2012 season concludes on the weekend of Feb. 17-19 with a program of selections from Monteverdi’s Madrigals of War & Love. Jeffrey Kurtzman and Warren Stewart contributed these program notes.

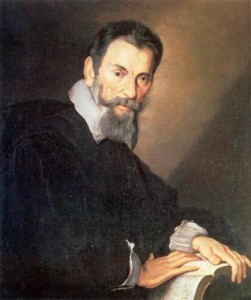

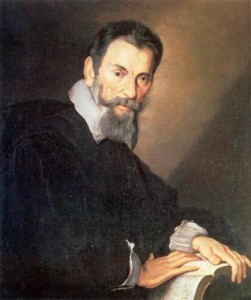

In 1638, Claudio Monteverdi, the seventy-one year-old music director of the ducal church of St. Mark’s in Venice, published his Eighth Book of Madrigals, the final collection of his secular music to be issued in his lifetime. He had last published a set of secular compositions in 1619, so the Eighth Book has a retrospective character, bringing together music written as early as 1608, and including one large work from 1624 and a variety of other compositions whose origins are unknown but which probably span the entire period 1619-1638. This unusually large collection was dedicated to Ferdinand III, the newly crowned Hapsburg Emperor in Vienna, whose mother was a member of the ducal family of the Gonazagas, former rulers of Mantua in northern Italy, where the early part of Monteverdi’s career had unfolded and to which he was still connected by various threads.

In 1638, Claudio Monteverdi, the seventy-one year-old music director of the ducal church of St. Mark’s in Venice, published his Eighth Book of Madrigals, the final collection of his secular music to be issued in his lifetime. He had last published a set of secular compositions in 1619, so the Eighth Book has a retrospective character, bringing together music written as early as 1608, and including one large work from 1624 and a variety of other compositions whose origins are unknown but which probably span the entire period 1619-1638. This unusually large collection was dedicated to Ferdinand III, the newly crowned Hapsburg Emperor in Vienna, whose mother was a member of the ducal family of the Gonazagas, former rulers of Mantua in northern Italy, where the early part of Monteverdi’s career had unfolded and to which he was still connected by various threads.

Monteverdi subtitled the Eighth Book Madrigali guerrieri et amorosi con alcuni opuscoli in genere rappresentativo(“Madrigals of war and love with some pieces in the theatrical style”), and the texts repeatedly expound the interlocking themes of love and war– the warrior as lover, the lover as warrior and the war between the sexes. The relationship between love and war had been a common Italian poetic conceit ever since the time of Petrarch in the 14th century, and had been given additional impetus by its prominence in Torquato Tasso’s late 16th century epic poem, Gerusalemme Liberata. The notion of lover as warrior was also central to the Neapolitan poet Giambattista Marino, who exerted a significant influence on Italian literature and aesthetics of the 17th century and whose poetry was set many times by Monteverdi.

The texts of several of the madrigals has been adapted to make specific reference to Ferdinand and to the Empire (River Nymphs of the Istrus, i.e. Danube; the ladies of the Germano Impero, etc.) but the overall theme of the collection was influenced by the role of the Hapsburg’s in the ongoing conflict now known as The Thirty Years War. The younger Ferdinand’s interest in the arts and music (he was a reasonably good composer himself and a patron of Froberger, Valentini, and of course Monteverdi.) Shortly before his accession to the throne, Ferdinand, together with his Spanish cousin, also a Ferdinand, were credited with capture of Donauwörth and Regensburg, and the defeat the Swedes and their Protestant allies at the Battle of Nördlingen. As head of the peace party at court, he helped negotiate the Peace of Prague in 1635 that was thought, sadly incorrectly, to be the end of the dreadful conflict. These events may have contributed to the triumphalism that permeates the Eighth Book and the sense that glorious military victories would lead to leisure and more amorous pursuits.

Monteverdi affixed an explanatory preface to the Eighth Book, a theoretically important, though sometimes confusing account of what he had tried to achieve in this music. The composer describes three emotional levels, which he also calls styles. Two of these, the “soft” style (stile molle) for languishing and sorrowful emotions, and the “tempered” style (stile temperato) for emotionally neutral recitations, he says had long been in use. But the third style, the “agitated” style, (stile concitato), Monteverdi claims to have invented himself. The musical depiction of this style consists of very rapid reiterations of the same pitch on string instruments, like a modern measured tremolo, and equally rapid reiterations of the supporting chord in the harpsichord or other continuo instrument. Such repeated notes and repeated chords had, in fact, been frequently used in compositions depicting battles for nearly a century, but for Monteverdi the stile concitato meant more than merely a musical metaphor for the rapid physical activity of fighting. It was also a specific emotional style–a musical means for interpreting the emotional agitation of the protagonists and conveying that agitation to the audience. The stile concitato, therefore, serves both a pictorial and a psychological function in Monteverdi’s music.

Magnificat’s program will follow the structure and order of Monteverdi’s publication, the selections in the first half are drawn from the Canti Guerrieri, or Songs of War and the second from the Canti Amorosi, or Songs of Love. The two halves open, like the two parts of the collection, with sonnets announcing, respectively, the themes of war and love. While the sonnet Altri canti di Marte was a pre-existing poem from Marino’s Rime (1602), it’s parallel in the first half, Altri canti d’Amor, seems to have been newly written for this collection and is clearly an imitation of Marino’s sonnet. After the two quatrains of Altri canti d’Amor that contrast themes of love and of Mars, the text of the sestet praises the dedicatee Ferdinand III. In addition to the usual pair of violins, Monteverdi introduces a quartet of viols when the text addresses the new Emperor and extols his lofty valor. This may have been a specific allusion to the large string ensembles favored by Viennese court composers of the time as the viola da gamba had gone out of fashion in Italy by the time Monteverdi was assembling his Eighth Book.

Altri canti d’Amor is followed, as in Monteverdi’s publication, by the most complex and sophisticated of Monteverdi’s large-scale madrigals from the Eighth Book,Hor che’l ciel e la terra. This madrigal sets, in two parts, the entirety of Petrarch’s 164th poem from the Canzoniere, a sonnet replete with Petrarchan contrasts and oxymorons. But Petrarch’s contrasts, as described by Pietro Bembo in the Prose della volgar lingua, are brought into harmony and smoothed over by mellifluous sounds and varied, rolling rhythms of his highly refined poetic style. This is easily seen in Petrarch’s fifth and sixth lines, where the most abrupt semantic juxtapositions are couched in an elegantly structured and alliterative sentence that draws attention away from the contrasts toward their union in a highly stylized and carefully crafted poetic conception. Resemblances of rhyme, of rhythm, of line lengths and stanzaic structure, and especially resemblances of sonority all serve to overcome the semantic contrasts. While earlier settings of this sonnet, notably Arcadelt’s famous account, emphasize this harmony and integration of oppositions, Monteverdi’s seizes upon the contrasts as the means for creating rhetorical statements and musical icons that can serve as the constructive basis for his composition. Indeed, contrasts as a means of expressing rhetoric and emotion permeate the entire collection and call to mind Monteverdi’s observation in the publication’s preface “that it is contraries that deeply affect our mind, the goal of the effect that good music ought to have.”

Two warrior-themed madrigals follow. The first, Se vittorie si belle, has been identified by John Whenham as the work of Fulvio Testi, a diplomat and poet in the Estense court in Modena and a literary follower of Marino. It was most likely written in the 1620s. The second warlike madrigal, Ogni amante e guerrier, was likely written specifically for inclusion in the Eighth Book with its topical references to Ferdinand. Notably for the extended bass solo in it’s second part featuring the repeated notes associated by the composer with the “agitated” style, Ogni amante e guerrier sets a slightly modified text by Ottavio Rinuccini. A similar musical depiction of warfare is found in the sonata La Gran Battaglia by the Modenese composer Marco Uccellini will separate the two madrigals in Magnificat’s program.

Altri canti di Marte, he sonnet that opens the second part of the Eighth Book and introduces the Canti Amorosi, clearly served as the model for it’s counterpart in the first half and is in some ways a mirror image, establishing first the themes of war that will be left to others before turning to more amorous matters. Here instead of Ferdinand, the poem addresses Love’s “warrior maiden” (guerriera) who has wounded the poet not with the weapons of war, but with her glances and soft tresses. Two lighter madrigals will follow, the five voice Dolcissimo usignuolo and the pastoral trio Perché te’n fuggi, o Fillide.

For the Lamento della Ninfa, one of the most passionate and moving works in the collection, Monteverdi again turned to Rinuccini. The poem, Non havea Febo ancora, published a year after the poet’s death in 1621, echoes the famous Lament of Arianna from the lost 1608 opera for which Rinuccini was the librettist, and Monteverdi chooses the same descending fourth ostinato figure for his setting of this lament. Massimo Ossi has shown the poem to be in the ‘strophic canzonetta’ form associated with Gabrielo Chiabrera, with stanzas composed of four alternating seven and six syllables lines followed by a rhymed couplet refrain. However, in contrast to Chiabrera’s convivial and amatory verse, Rinuccini’s canzonetta is a dramatic narrative, set as a dialogue between a forsaken nymph and a trio of observers. Monteverdi modifies Rinuccini’s poem considerably: the words of the nymph are set apart, framed by trios for male voices, and the refrain, rather than occurring after each stanza, is used to punctuate and comment on the nymph’s plaint. Monteverdi also provides performance directions with respect to tempo: the opening and closing trios are to be sung according to the beat of the hand, i.e., in a steady tempo, while the lament itself is to be sung ‘according to the affections of the soul and not to the beat of the hand,’ suggesting that the tempo and pacing of the lament are to follow the rhetorical and emotional nuances of the nymph’s complaint.

Rinuccini originally wrote Volgendo il ciel, a pair of sonnets, one tailed, one regular, in honor of Henri IV of France. In the first sonnet–it’s text modified for its new dedicatee and sung by a tenor with instrumental ritornelli–the poet sings of the new era of peace that will accompany the new Emperor and calling on the nymphs of the Danube to join their nimble feet in dance. The second sonnet, set a galliard-like ballo for five voices with violins, repeats the final four lines of the first as its first quatrain and continues in the same spirit, extolling the beauty of nature and their reflection in the exalted honor of the Emperor. Between the quatrains and sestet, Monteverdi suggests that “a canario, passo o mezzo or some other balletto” be performed and we will oblige with the Balletto Primo of Biagio Marini, a virtuoso violinist and composer who worked in Venice as well as many other courts in Europe over the course of his long career.

This review by Joshua Kosman was published in the San Francisco Chronicle on Dec. 11, 2012.

This review by Joshua Kosman was published in the San Francisco Chronicle on Dec. 11, 2012.