Celéste flamme, ardent amour

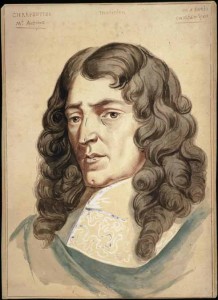

In 1670, upon returning to France from his studies with Carissimi in Rome, Marc-Antoine Charpentier became a member of the household of Marie de Lorraine, called Mademoiselle de Guise. One of the wealthiest women in Europe, and a princess in rank, Mlle. de Guise chose to live in Paris independent of the intrigues and obligations of court life under Louis XIV. She was a passionate lover of music, and maintained an ensemble of musicians, less opulent than that to be found at court, but highly admired by the Parisian connoisseurs of the time. The ensemble was made up for the most part of young people from families long under the protection of the Guise who, having come to live with Marie de Lorraine first as maids or companions, demonstrated some talent or interest for music. They were given lessons and eventually granted the status of musicians-in-ordinary, taking part in the devotional services at the private chapel and in the frequent private concerts at the Hôtel de Guise. The ensemble, although it included some salaried male singers and one member of a musical family (Ann Nanon Jacquet sister of the famous Elizabeth Jacquet de la Guerre), was fundamentally amateur and it is extraordinary that it should have developed to the extent that the journalMercure Galant in 1688 wrote that the music of Mlle de Guise was “so excellent that the music of many of the greatest sovereigns could not approach it.”

In 1670, upon returning to France from his studies with Carissimi in Rome, Marc-Antoine Charpentier became a member of the household of Marie de Lorraine, called Mademoiselle de Guise. One of the wealthiest women in Europe, and a princess in rank, Mlle. de Guise chose to live in Paris independent of the intrigues and obligations of court life under Louis XIV. She was a passionate lover of music, and maintained an ensemble of musicians, less opulent than that to be found at court, but highly admired by the Parisian connoisseurs of the time. The ensemble was made up for the most part of young people from families long under the protection of the Guise who, having come to live with Marie de Lorraine first as maids or companions, demonstrated some talent or interest for music. They were given lessons and eventually granted the status of musicians-in-ordinary, taking part in the devotional services at the private chapel and in the frequent private concerts at the Hôtel de Guise. The ensemble, although it included some salaried male singers and one member of a musical family (Ann Nanon Jacquet sister of the famous Elizabeth Jacquet de la Guerre), was fundamentally amateur and it is extraordinary that it should have developed to the extent that the journalMercure Galant in 1688 wrote that the music of Mlle de Guise was “so excellent that the music of many of the greatest sovereigns could not approach it.”

It was in this intimate and secure setting that Charpentier composed the Pastorale sur la naissance de Notre Seigneur Jésus Christ. He was composing for people with whom he lived, daily took his meals, and worked as a peer, himself singing alto in the choir; these were people with whom, to judge by the designation of parts in the manuscripts -Isabelle, Brion, Carlié, etc. – Charpentier was on a comfortable first name basis. Phillipe Goibault DuBois, another member of the Guise household who was actually the director of the ensemble and a scholar recognized by the Académie Française for his translations of Cicero and St. Augustine, most probably wrote the text of the Pastorale. The possibility that the Pastorale was intended to accompany a traditional Christmas pageant is raised by the list of acteurs on the title page of the manuscript: along with the shepherds and angels are the names of Mary and Joseph, who have no singing parts anywhere in the piece. Charpentier’s biographer Catherine Cessac has suggested that the Pastorale may have been intended for performance at a school for the education of poor girls supported by Mlle de Guise. It is easy to imagine costumed young girls arranged in traditional tableaux vivants during this musical expression of the Christmas story.

In any case, there is no doubt that the Pastorale was composed as a succession of scenes and performed each Christmas from 1684 to 1686, though not with the same scenes each year: Charpentier’s directions in the manuscript give three different arrangements. This presents an interesting dilemma – are there three distinct “pieces”, representing successive improvements, or did Charpentier view the scenes as modular elements which could be variously combined or omitted for each different Christmas celebration? Magnificat has chosen this last approach – our program will use the opening scenes common to all three arrangements which tell the story up to the appearance of the angels to the shepherds; the scene at the crèche comes from the1685 manuscripts, and the closing scene showing the shepherds on their way home at dawn comes from the 1686 version.

Stylistically, the Pastorale is one of Charpentier’s most brilliant and varied works, containing dialogues, ensembles, instrumental dances, and exquisite choral writing, but the unifying force throughout is the composer’s extreme sensitivity to the text and his technical mastery and imagination in setting it. The influence of Carissimi can be heard in the strong characterization given to the old shepherd, and in the dramatic dialogue between the angel and the shepherds. At other moments in the piece, such as the rondeau Niege, glaçons, frimats, Charpentier’s inclination toward classical French symmetry is clearly felt. The overture is a splendid example of Charpentier’s mastery of instrumental writing; chromaticism and dissonance alternate with the gaiety of dance forms to express the Advent themes of darkness and light, despair and hope.

For an appreciation of the scenes and images of this Pastorale, we need to look to the tradition, long established by Charpentier’s time, of noëls. Beginning in the mid-sixteenth century, the words for these simple songs were published in inexpensive, sloppily produced editions called bibles de noelz, and were circulated throughout the provinces by colporteurs or itinerant peddlers and booksellers. Contemporary writers describe these bibles as being found on the hearth in every peasant cottage: greasy, yellowed, and dog-eared. The melodies were pre-existing, anonymous, orally transmittedvaudevilles. Sebastian de Brossard in his music dictionary of 1703 defined noëls as “certain songs in honor of the birth of Jesus Christ set to vaux de villes, or common tunes, that everybody knows.” The melodies were never notated in these popular bibles; it was enough to mention the first few words of the original song, called the timbre, at the beginning of the poem. The best known noël to English audiences Un flambeau set to a timbre that was originally a drinking song Qu’il sont doux, bouteille jolie, attributed variously to Charpentier and Lully. Although some significant poets contributed to the genre, the poems were usually anonymous, written by schoolteachers, priests, or organists in every town, often in dialect and most probably spontaneously improvised to include the names of friends and neighbors. The texts are often wonderfully exuberant, describing the earthly festivities that accompany the divine birth, including recipes for food to be brought to the party, and a certain amount of practical joking. These noëls increased in popularity throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and made their way into liturgical services, to the displeasure of church authorities. In 1725 the Council de la Province d’Avignon prohibited the singing of noëls in church on the grounds that they “debased the holy mysteries by mixing them with comic things and profane chattering and games.” This disapproval did not stem the popularity of the noëls and bibles de noelz continued to be produced even after the Revolution.

Charpentier shared his contemporaries’ love for these humble songs; without doubt he, like Frenchmen of all classes, had sung them all his life. It isn’t surprising then that the Pastorale is imbued with the same peculiar sense of realism combined with piety that one finds in the noëls, nor that certain images from the noëls find their way into the more refined work – for example, the warming breath of the innocent animals, concern for cold weather, and the sense of rustic festivity. Charpentier’s instrumental settings of noëls were probably intended for general use at the Hôtel de Guise, but were incorporated into the liturgy as well.

Adapted from program notes written by Susan Harvey in 1996 for Magnificat’s performances of Charpentier’s La Pastorale sur la Naissance de Nostre Seigneur.