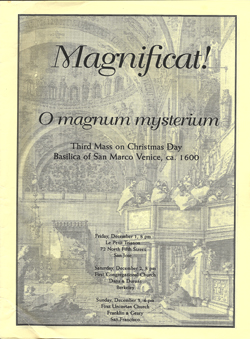

Magnificat’s seventh season included a full-scale puppet opera, another program of music by Buxtehude, a journey to the New World, and our second production of Monteverdi’s extraordinary Vespers of 1610.

Magnificat’s seventh season included a full-scale puppet opera, another program of music by Buxtehude, a journey to the New World, and our second production of Monteverdi’s extraordinary Vespers of 1610.

The sold-out performances of the opera parody La Grandmére amoureuse in January 1998 prompted a search for other surviving puppet operas and we quickly began preparing a performance score of Jacopo Melani’s Il Girello. Written and first performed in 1668, Il Girello featured a libretto by Filippo Acciaiuoli in 1668 and a prologue by Alessandro Scarlatti. The opera was immensely successful and saw many revivals into a performance with life-size puppets in Venice in 1682. It was an obvious choice for a follow-up collaboration with the Carter Family Marionettes.

Neal Rogers, Judith Nelson, Randall Wong and Peter Becker perform "Il Girello"

In his review of one of the San Francisco performances, Joshua Kosman of the San Francisco Chronicle aptly described Girello as “an unalloyed de light, a fluid blend of high and low art” and “a shameless crowd-pleaser.” Unique in the history of Magnificat’s concert series, the Girello production was extended to two weekends with five series performances and an additional concert presented by the Redwoods Arts Council in Occidental CA.

For the third season in a row, Magnificat was invited to perform the Christmas concert o0n the San Francisco Early Music Society series with another program devoted to the music of Dietrich Buxtehude. Like the program that opened Magnificat’s sixth season, the focus was on intimate chamber cantatas with a string band of two violins and two violas.

This was the first Magnificat production to be reviewed by the brand-new classical music website San Francisco Classical Voice. Anna Carol Dudley observed that “there was There is something felicitous about presenting an ensemble named Magnificat in a performance of Advent music.” Of course, while the notion of being “online” was still relatively new in 1998, SFCV went on to become a fixture for music-lovers in the Bay Area.

In January 1999, Magnificat ventured to the New World in a recreation the the festivities surrounding the Feast of Epiphany (oe Twelfth Night) in what is now called Jalisco Mexico. In 1587, Fray Alonso Ponce, a colonial official was present at a fiesta on the Feast of the Epiphany, and described in considerable detail a play that was performed after Mass that was an annual tradition. For Magnificat’s “reconstruction,” imagined to be in the late 17th century, we used Spanish verses that had been handed down from the colonial period.

The play features many stock characters inherited from Spanish 17th-century theatre; the lazy, gluttonous Bartolo, the 200 year old, whip-cracking Ermitaño (Hermit) given to sudden displays of dancing, the uncouth Ranchero, and Bato, the managerial Everyman. The shepherd’s play, which was realized by members of the comedy troupe L.O.C.O.S. (Latinos or Chicanos or Something,) with Magnificat performing villancicos at several points. The music for the ordinary was Juan Gutiérrez de Padilla’s Missa “Ego flos campi” and the motet Hostes Herodes by Pablo de Escobar with chant drawn from the Graduale Domicale of Pedro Ocharte (1572.)

The season concluded with Magnificat’s second production of Monteverdi’s monumental Vespers of 1610. Returning to this collection of extraordinary music was a pleasure for all involved. For this production Magnificat incorporated Monteverdi’s psalms, motets and Magnificat into the liturgy for the Feast of Annunciation andalso included Alessandro Grandi’s motet Missus est Gabriel.

The season concluded with Magnificat’s second production of Monteverdi’s monumental Vespers of 1610. Returning to this collection of extraordinary music was a pleasure for all involved. For this production Magnificat incorporated Monteverdi’s psalms, motets and Magnificat into the liturgy for the Feast of Annunciation andalso included Alessandro Grandi’s motet Missus est Gabriel.

The first of the three concerts was at Stanford’s Memorial Church and a panel discussion on performance practice issues related to Monteverdi’s 1610 Vespers was organized through the music departments of Stanford and UC Berkeley that included Jeffrey Kurtzman, Herb Myers, Doug Kirk, Ray Nurse and Warren Stewart.

In June 1999, Magnificat was invited by the Seattle Early Music Guild to present a revival of our 1998 production of La Grandmere amoureuse at two venues in Seattle. Once again we were joined by The Carter Family Marionettes, along with poultry from a Seattle Chinese market, and the response to the six performances was as enthusiastic as it had been in the Bay Area. The Seattle Times wrote: “the singers sounded great, the actor-marionettes were a hoot, and the chamber musicians played well. But it was the live poultry that brought down the house.”

Over the course of the season, artistic directors Susan Harvey and Warren Stewart led ensembles that included Carlos Aguirre, Peter Becker, Jaime Bolaños, Melvin Butel, Chris and Stephen Carter, Bruce Chessé, Elijah Kenn Chester, Mark Daniel, Hugh Davies, Paul Del Bene, Rob Diggins, John Dornenburg, Jolianne von Einem, Ruth and Steve Escher, Arturo Fernandez, Ken Fitch, Boyd Jarrell, Jeff Kabatznik, Jennifer Ellis, Doug Kirk, Susan Rode Morris, Herb Myers, Judith Nelson, Ray Nurse, Vicki Gunn Pich, Mack Ramsey, Neal Rogers, Michael Sand, Richard Savino, Sandy Stadtfeld, Bill Wahman, Scott Whitaker, David Wilson, and Randall Wong.