Monteverdi's Song of Mary and 'Re-Animation'

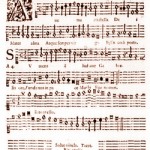

Monteverdi's Setting of the Hymn 'Ave maris stella'

Sonata à 8 sopra Sancta Maria ora pro nobis (1610)

The Sonata sopra Sancta Maria borrows the opening phrase from the Litany of the Saints and reiterates it in the soprano voice eleven times over a sonata for eight instruments. In general, the structure of the Sonata resembles, on a very large scale, that of a typical late sixteenth-century instrumental canzona, comprising a series of loosely related sections with repetition of the opening material at the end. As with the adaptation of the L’Orfeo toccata to Domine ad adiuvandum, a liturgical chant is superimposed on the instrumental composition, which could easily stand alone.

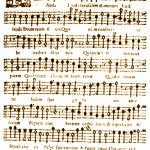

Montverdi's Setting of the Psalm Laetatus sum (1610)

Whereas the structure of Dixit Dominus, Laudate pueri, Nisi Dominus, and Lauda Ierusalem is centered around reiterations of the psalm tone in each verse, the formal organization of Laetatus sum does not depends on the cantus firmus, but rather on the disposition of the text over a series of repeated bass patterns.

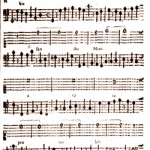

Monteverdi's Setting of the Psalm Laudate pueri (1610)

Monteverdi's setting of Laudate pueri (1610) is scored for eight voices, but here, in contrast ith his technique in Nisi Dominus and Lauda Ierusalem, Monteverdi rarely divides the ensemble into antiphonal four-voice combinations, preferring instead to pair voices in the same register. Throughout the psalm, Monteverdi is extremely flexible in his treatment of the plainchant. The psalm tone (tone 8 with finalis g) migrates freely from voice to voice, is transposed and is absent altogether in some passages. Nevertheless, each verse of the psalm appears at least once in plainchant. The treatment of the psalm tone at the beginning of Laudate pueri resembles that at the opening of Dixit Dominus: after initial solo intonations in a tenor voice (quintus), the psalm tone combines with a countersubject to evolve a steadily expanding imitative texture. Even the countersubject is similar to the one at the beginning of Dixit Dominus. Whereas this process encompassed ...

Monteverdi's Setting of the Psalm Dixit Dominus (1610)

After its opening verse, Monteverdi's 1610 setting of Dixit Dominus alternates between falsobordone settings of the chant (tone 4 with finalis e) and imitative textures built over the cantus firmus in the bass. Each falsobordone is followed by an instrumental ritornello. The doxology then concludes with a solo tenor intonation of the psalm tone and a six-voice polyphonic chorus, balancing the opening verse in symmetrical construction. Throughout the psalm, only the melismas that conclude each half verse (typical for falsobordoni) and the ritornellos are free of the chant. Within this scheme, Monteverdi varies the context of the chant in several different ways. In the falsobordoni themselves, the first half-verse is presented on an a minor chord (A major for verse 6), while the second half-verse is a steplower on a G major triad. In the alternate verses 3, 5, and 7, the chant, transferred to the bass in half and quarter ...

The Whole Noyse to Perform with Magnificat

It is a pleasure to be working together again with The Whole Noyse in Magnificat's performances of Monteverdi's 1610 Vespers. In numerous collaborations over the past two decades, I have been consistently impressed with their musicianship and impeccable ensemble playing and Steve, Richard, Sandy and Herb have all become dear friends and trusted musical colleagues. The Whole Noyse will be joined by cornettist Kiri Tollaksen and frequent collaborator trombonist Ernie Rideout in our Vespers performances. The Whole Noyse has collaborated with Magnificat from our very first season in 1992, when they joined for a series of memorable performances of Schütz' Weihnachtshistorie, co-presented by the San Francisco Early Music Society. In 1994, they joined in our staged production of Cavalieri's Rappresentatione di Anima e di Corpo, which we subsequently recorded for Koch International. No one who was present will forget the infamous Halloween recording session that stretched into the wee hours of ...

Monteverdi's Setting of the Psalm Lauda Ierusalem (1610)

The 'Specialness' of Monteverdi's Vespers

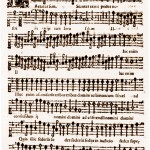

Monteverdi's Setting of Nisi Dominus (1610)

In each of the psalm settings of Montverdi’s 1610 Vespers the varying contexts of the cantus firmus (in each case, the psalm tone) help to define the structure of the psalm itself. The simplest organization is found in the cori spezzati setting of Nisi Dominus, which exhibits a continuous cantus firmus (sixth tone with finalis f) in the tenor part of each of the two five-voice choirs.

Re-Discovering Monteverdi's Vespers of 1610

With Monteverdi’s 1610 Vespers, Magnificat is approaching music that is generally familiar to our audience — many of whom have even sung the piece — and each of the musicians involved can list multiple performances of the work on their resumes. Yet turning to Monteverdi’s familiar music together is no less a revelation than any premiere, especially in the company of musical friends that bring such a breadth of experience with them to the performances.

Polyphonic Vespers Music Before Monteverdi

Forty years ago, virtually nothing was known about polyphonic music for the Office except for the 1610 Vespers of Claudio Monteverdi, which had been receiving significant scholarly attention since shortly after World War II. Today, not only have a number of critical editions of Vesper publications from Italy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries been issued in various series, but a variety of scholars have researched the relationship between published and manuscript liturgical music and the monastic institutions and their friars and nuns that produced and performed this music.

Monteverdi's Unsuccessful 'Audition' in Rome

As early as the Fall of 1608 Monteverdi had discussed the possibility of leaving Mantua and his publication of a monumental Mass and Vespers in 1610, with a dedicate to Pope Paul V was clearly an attempt to promote his services. In that year, with his collection in tow, Monteverdi traveled to Rome, where he hoped to achieve two results: an audience with the Pope to enable him to offer his sacred collection in person, and a free place for his son Francesco. (Monteverdi was a widower of over two years at that point.) In a letter from that month he wrote to Cardinal Ferdinando Gonzaga: "'in the Roman seminary with a benefice from the church to pay his board and lodging, I being a poor man. But without this favor I could not hope for anything from Rome to help Franceschino, who has already become a seminarian in order to ...

Masterworks and Context

It is one of the paradoxes of musicological research that we generally have become acquainted with a period, a repertoire, or a style through recognized masterworks that are tacitly or expressly assumed to be representative. Yet a 'masterpiece', by definition, is unrepresentative, unusual, and beyond the scope of ordinary musical activity. A more thorough and realistic knowledge of music history must come from a broader and deeper acquaintance with its constituent elements than is provided by a limited quantity of exceptional composers and works. Such an expansion of the range of our historical research has the advantage not only of enhancing our understanding of a given topic, but also of supplying the basis for comparison among those composers and works that have faded into obscurity and the few composers and 'masterpieces' that have survived to become the primary focus of our attention today. Only in relation to lesser efforts can ...

Monteverdi's Vespers - the Crest of a Wave

The second half of the sixteenth century witnessed a growth in published Italian Vespers repertoire, a growth that increased dramatically as the century approached its end. In the first decade of the new century, the number of extant prints once again augments by approximately 50 per cent. I have located more than 150 publications from this period, about two thirds of them issued between 1605 and 1609. From the year 1610 alone, aside from Monteverdi's print, I have been able to trace an additional 25 surviving collections containing vesper music. Of the total of nearly 180 publications from these eleven years, 24 are reprints. By this time, the number of vesper publications has exceeded the number of mass prints from the same period. It is clear that by the first decade of the century, a major shift in emphasis had taken place in the public services of the Catholic Church ...

"With various and diverse manners of invention and harmony"

"Monteverdi is having printed an a capella Mass for six voices, of much study and labour, since he was obliged to manipulate continually, in every note through all the parts, always further reinforcing, the eight motifs that are in the motet In illo tempore of Gombert. And he is also having printed together [with it] some vesper psalms of the Virgin with various and diverse manners of invention and harmony, and everything over a cantus firmus, with the intention of coming to Rome this autumn to dedicate them to His Holiness. He is also in the midst of preparing a group of madrigals for five voices, which will consist of three laments: that of Arianna, still with its usual soprano, the lament of Leandro and Hero by Marini, the third, given him by His Highness, about a shepherd whose nymph has died. The words [are] by the son of Count ...

Monteverdi and Musical Coherence

The musical coherence of Monteverdi's seconda prattica compositions has often been overlooked by taking too literally his brother Giulio Cesare's famous declaration that in the new style 'it has been his intention to make the words the mistress of the harmony and not the servant.' Monteverdi and his brother, for the sake of argument and without enough time to develop the thesis at greater length, oversimplified the issue in the Dichiaratione of the 1607 Scherzi musicali. While Monteverdi certainly took the text as his point of departure as well as the ultimate rationale for many features of his madrigals, motets, and dramatic compositions, he never became a slavish imitator of words not an ingenious inventor of musical metaphors, even though madrigalisms are readily apparent in his music. Te balanced union of textual and musical considerations took different forms in the stile rappresentativo and the polyphonic and concerto madrigals and motets. Morever,m ...

Monteverdi's Successful Audition

The sheer variety and magnificence of Monteverdi's 1610 collection is breathtaking, and in 1613, music from the Vespers may have served as part of Monteverdi's successful audition for the position of maestro di capella at the ducal church of St. Mark's in Venice, the most important church job in all of northern Italy. In this 1610 print, which also includes a conservative, even archaic, six-voice polyphonic mass, Monteverdi gathered the most diverse examples of modern musical style imaginable for his Vespers. Introducing the Vesper service is the solo plainchant versicle (Deus in adiutorium) followed by its massive, fanfare-like response with the full choir supported by a large instrumental ensemble of strings and brass. This response was reconstituted out of the fanfare introduction to Monteverdi's own first opera of 1607, Orfeo. Following the opening of the service, virtuoso solo and few-voiced motets sit side-by-side with the psalms featuring ...

Monteverdi's Work Sample

Monteverdi's Mass and Vespers of the Blessed Virgin of 1610, his first major publication of sacred music, is dedicated both to the Virgin, whom his patrons, the Gonzaga dukes of Mantua, claimed as the special protectress of their city, and to Pope Paul V, whose envoy had proclaimed a plenary indulgence in Mantua’s principal church of Sant-Andrea in 1607. It seems apparent that with this publication Monteverdi was seeking to establish himself as a suitable candidate for a position of maestro di capella in a major Italian church—his ticket out of the debilitating pressures and penury of his employment at the Gonzaga court which had even caused him unsuccessfully to seek dismissal from court service in 1608.