Coming off a triumphant performance at the 2002 Berkeley Festival and the release of a second recording of music by Chiara Margarita Cozzolani, Magnificat’s eleventh season featured music by Charpentier, Stradella, Isabella Leonarda and Buxtehude, as well as a conference on Women and Music in Italy and our first appearance in New York.

Working with Charpentier scholar John Powell, Magnificat opened the season with a program of music the composer had written for the Parisian theatre. In our first season we had presented incidental music that Charpentier had written mostly from plays by Moliére also based on Powell’s work. For this program music we selected music from three plays written in the 1670s: Circé, Les fous divertissements and La Pierre philosophale.

Working with Charpentier scholar John Powell, Magnificat opened the season with a program of music the composer had written for the Parisian theatre. In our first season we had presented incidental music that Charpentier had written mostly from plays by Moliére also based on Powell’s work. For this program music we selected music from three plays written in the 1670s: Circé, Les fous divertissements and La Pierre philosophale.

When, in 1673, Charpentier became the principal composer to the King’s Troupe (Troupe du Roy), he became involved in the ongoing struggle between the company’s director and chief playwright, Jean-Baptiste Molière, and the composer Jean-Baptiste Lully. Throughout the 1660s, Molière and Lully had worked closely in providing for the king’s entertainment a series of multi-generic experiments that combined theater, ballet, vocal numbers, choruses, and machine effects. But by the spring of 1672 Lully had decided that his own future lay in opera. Having witnessed the successes of Perrin and Cambert with pastoral opera, Lully set about obtaining the royal opera privilege and, thereafter, a series of draconian decrees designed to protect his monopoly and reduce his musical competition. Molière soon found another musical colleague in Charpentier, recently returned from Rome and his studies with Giacomo Carissimi. The revivals of earlier collaborations with Lully (La Comtesse d’Escarbagnas, Le Mariage forcé) with new music by Charpentier led to a full-scale comedy-ballet, Le Malade imaginaire. This devastating musical satire would be the playwright’s last work—for during its fourth performance Molière, playing the leading role of the hypochondriac Argan, fell ill during the finale and died at his home shortly thereafter. Thereafter, musical life in Parisian theater was a struggle to survive in the face of Lully’s active opposition.

In his review for the San Francisco Classical Voice, Joseph Sargent wrote that “Magnificat’s artistic director Warren Stewart elicited a finely crafted performance, the precision and musical expression outstanding… a quartet of vocalists gave Charpentier’s music a nuanced, sensitive reading … from the opening overture to the final chorus, the instrumental consort was impressive in its precision. The seven-member band of winds, strings and continuo displayed tight ensemble work throughout the program, with impeccable attacks, perfect intonation and precise phrasing.”

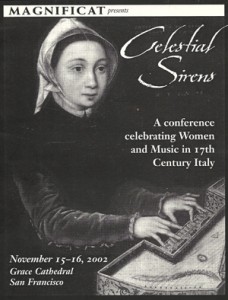

In November of 2002, Magnificat hosted a conference on women and music in 17th Century. The conference was held at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco and included papers read by four scholars whose work has illuminated our understanding of the emerging role of women as musicians and composers.The conference opened with Reflections and New Findings on Cozzolani’s Music., by Robert Kendrick of the University of Chicago and was followed by Poems for Nuns: Models of Sanctity and Religious Practice in Serafino Razzi’s Legends by Gabrielle Zarri of the University of Florence, Italy. After a discussion the conference continued with Washington University professor Craig Monson’s paper Putting the Convent Musicians of Italy in Their Place, which included some of the material found in his 2010 book Nuns Behaving Badly. In the afternoon two more papers were given: Ann Matter of the University of Pennsylvania spoke about the rich tradition of Christian allegorical and spiritual language in the dialogues of Cozzolani and other nun composers in her paper Sacred Dialogues in 17th Century Italian Women Composers’ Spirituality and Colleen Reardon of Binghamton University read Persuasions: or You Can Catch More Nuns With Music, about the custom of constraining a young woman to enter the convent against her will was both roundly denounced and widely practiced throughout early modern Italy. The conference included two programs performed by Magnificat, a vespers with music by Cozzolani in the choir of Grace Cathedral and a mixed program of motets by several women composers at Trinity Episcopal Church.

In November of 2002, Magnificat hosted a conference on women and music in 17th Century. The conference was held at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco and included papers read by four scholars whose work has illuminated our understanding of the emerging role of women as musicians and composers.The conference opened with Reflections and New Findings on Cozzolani’s Music., by Robert Kendrick of the University of Chicago and was followed by Poems for Nuns: Models of Sanctity and Religious Practice in Serafino Razzi’s Legends by Gabrielle Zarri of the University of Florence, Italy. After a discussion the conference continued with Washington University professor Craig Monson’s paper Putting the Convent Musicians of Italy in Their Place, which included some of the material found in his 2010 book Nuns Behaving Badly. In the afternoon two more papers were given: Ann Matter of the University of Pennsylvania spoke about the rich tradition of Christian allegorical and spiritual language in the dialogues of Cozzolani and other nun composers in her paper Sacred Dialogues in 17th Century Italian Women Composers’ Spirituality and Colleen Reardon of Binghamton University read Persuasions: or You Can Catch More Nuns With Music, about the custom of constraining a young woman to enter the convent against her will was both roundly denounced and widely practiced throughout early modern Italy. The conference included two programs performed by Magnificat, a vespers with music by Cozzolani in the choir of Grace Cathedral and a mixed program of motets by several women composers at Trinity Episcopal Church.

In December, Magnificat once again benefitted from the musicological research of another scholar, working from editions of Stradella’s two Christmas Cantatas prepared by Eleanor F. McCrickard of the University of North Carolina. Details about the two Christmas cantatas are scanty. It is not known for whom they were composed, where they were first performed, or who the poets were. One would like to think they were a part of the sixty-five-year tradition of music in the papal chamber in Rome from 1676-1740 for which a composer was invited to provide a cantata on the Christmas subject for a performance on Christmas Eve. No proof exists, however, that either of them was used. Other evidence—handwriting, paper, style—indicates that Si apra al riso ogni labro was for Modena and Ah! troppo è ver, for Rome with composition in the1670s, Si apra being the earlier of the two. The subject in each work is treated in a different manner, from the somewhat pensive Si apra al riso ogni labro to the dramatic Ah! troppo è ver. Magnificat also performed one of Stradella’s instrumental sonatas on the program.

Magnificat next turned to the music of another remarkable woman from the 17th Century, Isabella Leonarda, an Urseline nun and prolific composer who lived in a convent in Novarra during the second half of the century. The program was built on liturgy for the Feast of Purification and featured settings of four psalms and the Magnificat by Isabella as well as several of her instrumental sonatas. Kerry McCarthy, writing for the San Francisco Classical Voice noted that “the rapport and energy among the musicians was evident throughout the evening.” Two recordings from this concert are available on Magnificat’s music page, with Catherine Webster featured in Isabella’s setting of Lætatus sum and Rob Diggins in her extraordinary solo violin sonata.

In March Magnificat was presented by the Music Before 1800 series in New York. The concert took place at Corpus Christi Church near Columbia University and the program, like the recording Vespro della Beata Vergine, was built around Second Vespers for the Feast of the Annunciation. The excellent acoustics of Corpus Christi and the very warm audience contributed to a very successful East Coast debut for Magnificat.

Magnificat’s season concluded with a revival of Buxtehude’s cantata cycle Membra Jesu nostri. As in our 1996 performances, Buxtehude’s setting of the Medieval poem Salve mundi salutare were interwoven with Johann Georg Ebeling’s setting of Paul Gerhadt’s German translation of the text. In the program notes artistic director Warren Stewart wrote “In Buxtehude’s cantatas and the chorales of Ebeling we are presented with something quite outrageous — the image of a lover embracing a broken and disfigured body, compassionately desiring to examine its wounds. To our modern sensibility it is shocking and revolting, or at the very least in questionable taste. Today we hide our wounded in institutions, and we are required, in the interest of productivity, to conceal our own wounds.” Commenting on the performance, the San Francisco Calssical Voice observed that “each of the five voices was lovely in its own right, but when they sang together, the resulting alchemy made the group a real pleasure to listen to.”

Over the course of the season Warren Stewart directed ensembles that included Elizabeth Anker, Peter Becker, Meg Bragle,Louise Carslake, Maria Caswell, Hugh Davies, Rob Diggins, John Dornenburg, Jolianne von Einem, Suzanne Elder Wallace, Jennifer Ellis, Ruth Escher, Andrea Fullington, Julie Jeffrey, Rita Lilly, Anthony Martin, Stephen Ng, Hanneke van Proosdij, Elisabeth Reed, Deborah Rentz-Moore, David Tayler, Catherine Webster, Scott Whitaker, David Wilson and Ondine Young.

2009-2010 was one of Magnificat’s most expansive seasons, featuring music by two remarkable women and two pioneers of the new music of the seventeenth century. The programs ranged from a puppet opera to a liturgical reconstruction and culminated with two appearance at the 2010 Berkeley Festival and Exhibition and the release of volume one of the complete works of Chiara Margarita Cozzolani.

2009-2010 was one of Magnificat’s most expansive seasons, featuring music by two remarkable women and two pioneers of the new music of the seventeenth century. The programs ranged from a puppet opera to a liturgical reconstruction and culminated with two appearance at the 2010 Berkeley Festival and Exhibition and the release of volume one of the complete works of Chiara Margarita Cozzolani.