In two decades of exploring 17th Century music I have been continually fascinated by the way compositional techniques, modes of expression and ideas of taste and style migrated across Europe. These stylistic journeys most often began in Italy and travelling northward and refracted into spectrum of national styles of the High Baroque. Perhaps because I have spent time as a foreigner recently, encountering different traditions and cultures and learning new ways of communicating, my awareness of the role that the exchange of ideas plays in the development of art and society has been especially keen. The programs Magnificat will present in 2013-2014 all focus on the exchange of techniques and ideas, the generational transfer and elaboration of tradition and the translation of style from one culture to another.

In two decades of exploring 17th Century music I have been continually fascinated by the way compositional techniques, modes of expression and ideas of taste and style migrated across Europe. These stylistic journeys most often began in Italy and travelling northward and refracted into spectrum of national styles of the High Baroque. Perhaps because I have spent time as a foreigner recently, encountering different traditions and cultures and learning new ways of communicating, my awareness of the role that the exchange of ideas plays in the development of art and society has been especially keen. The programs Magnificat will present in 2013-2014 all focus on the exchange of techniques and ideas, the generational transfer and elaboration of tradition and the translation of style from one culture to another.

Order Tickets Online – Download Mail Order Form

Few events had a more profound influence on the music of the 17th century than the changing of the guard that took place at the Basilica of San Marco with the death of Giovanni Gabrieli in 1612 and the arrival of Claudio Monteverdi from Mantua the following year. Though they never held the post of maestro di cappella at San Marco, Giovanni and his uncle Andrea nevertheless dominated the musical life of the Serene Republic for three decades. Their brilliant polychoral style was appealing and effective and they pioneered the use of obbligato instruments in the service of what we would now call orchestration to give their concertos color and affect in a way that was imitated across Europe. One of Giovanni’s many students from north of the Alps in his final years was Heinrich Schütz, who studied in Venice for four years and returned to Dresden shortly after his teacher’s death, missing Monteverdi’s arrival by a matter of months. But more on that in the next program.

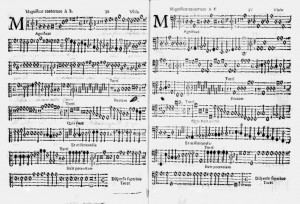

In his old age Giovanni began to incorporate some of the techniques associated with the ‘secunda prattica’, specifically an independent basso continuo and florid writing for solo voice. This is especially evident in some of the compositions included in his second volume of Symphoniae Sacrae, published posthumously in 1615. Similarly, while Monteverdi is most closely associated with the new music of the new century, he nevertheless took pains to demonstrate his mastery of the old polyphonic techniques, for example in the Missa in illo tempore, published along with his famous Vespers music in 1610 and the stile antico masses in his 1641 collection Selva morale et spirituale.

The blurring of compositional style represented by these two titans of Venetian music is central to Magnificat’s program on the weekend of December 20-22, for which we will join forces with The Whole Noyse in a co-production with the San Francisco Early Music Society. The program is built on a frame provided by the liturgy for the Christmas Mass but the music we will perform was unlikely to have been assembled for any specific event from the time. Rather we will combine the grandeur of Gabrieli with the passion and virtuosity of Monteverdi in a way that displays both the continuity and innovation reflected in the music of Venice at the beginning of the century.

In August 1628, Heinrich Schütz escaped war-ravaged Dresden and travelled to Venice, where he had studied with Gabrieli almost twenty years before. In a letter written after his return in late the next year, Schütz recalled “staying in Venice as the guest of old friends, I learned that the long unchanged art of composition had changed somewhat: the ancient rhythms were partly set aside to tickle the ears of today with fresh devices.” During his visit, he certainly heard such fresh devices in the madrigals and motets of Monteverdi and Grandi and in instrumental sonatas by Biagio Marini and Dario Castello. Marini’s eighth set of sonatas, subtitled “Curiose e Moderne Inventioni,” was published in Venice during Schütz’s stay in Venice, as was the Dresden Kappelmeister’s own collection of motets, his first set of Symphoniæ Sacræ.

The spirit of the “new music” Schütz heard in Venice continued to resonate in his music throughout his life and Magnificat’s program will reflect that resonance in a program that also features music of other composers who shared in the stylistic exchange. Schütz ‘borrowed’ (with full acknowledgement) some of Monteverdi’s music in his owncompositions, notably in the motet Es steh Gott auf, which appeared in the composer’s second set of Symphoniae Sacrae published in Dresden in 164_. But beyond direct quotations, much of the music Schütz wrote after his return to Dresden sparkles with the sunny brilliance Italy, though always with a marked German accent.

The program for our concerts on February 14-16 2014 centers on another generational exchange and the extraordinary tradition of the Bach family inherited by Johann Sebastian. Throughout the seventeenth century, so many of the organists and instrumentalists in the small towns of central Germany were Bachs that in the province of Thuringia the name ‘Bach’ was synonymous with the trade of musician. Bach’s obituary notice in 1750 observed that “Johann Sebastian Bach belongs to a family that seems to have received a love and aptitude for music as a gift of Nature to all its members in common.”

In October 1694, the nine-year-old Johann Sebastian travelled to Arnstadt for the wedding of his cousin, the highly respected Eisenach organist Johann Christoph Bach. The Bach family gathered frequently, but this occasion was exceptional in that Christoph’s teacher, the renowned organist and composer Johann Pachelbel was present and likely performed together with members of the Bach family. 1694 also saw the publication of a set of sonatas by the Dresden violinist Johann Paul Westhoff, in whose orchestra Bach would later perform as a teenager before accepting his first position as an organist in Arnstadt.

In this program Magnificat will explore the music of Bach’s ancestors that the young Bach may have heard during the wedding festivities and will feature cantatas and instrumental music by Sebastian’s cousins Johann Christoph and Johann Michael Bach as well as Pachelbel and Westhoff. The program is framed by cantata based on the chorale Christ lag in Todesbanden, opening with Pachelbel’s setting, which may have served as the model for the young Johann Sebastian Bach’s first masterpiece, which will conclude the concert.

Two cantatas on the program are preserved in a collection of manuscripts known to musicologists as Das Altbachisches Arkiv, or the “Archive of the Elder Bachs.” Sebastian treasured these manuscripts throughout his life, making annotations in the scores and performing some of the works as late as 1749, the year before his death. The archives passed on to his son Carl Phillip Emmanuel and later became part of the library of the Berliner Singakademie, which was so instrumental to the revival of Bach’s music in the 19th century. Thought to have been destroyed in the Second World War, the archives were recently re-discovered and Magnificat will be performing from editions based on these manuscripts.

I look forward to working with an extraordinary cast of musicians and friends including Peter Becker, Hugh Davies, Rob Diggins, John Dornenburg, Jillon Dupree, Jolianne von Einem, Paul Elliott, Katherine Heater, Laura Heimes, Dan Hutchings, Jennifer Ellis Kampani, Chris LeCluyse, John Lenti, Anthony Martin, Clifton Massey, Jennifer Paulino, Andrew Rader, Clara Rottsolk, David Wilson and The Whole Noyse,

The instrumental music on Magnificat’s Berkeley Festival program is drawn from Musiche sacre (Venice, 1656) by Monteverdi’s colleague at San Marco, Pier Francesco Cavalli. A musician of the highest caliber, Cavalli’s virtuosity as an organist was compared to Frescobaldi and in 1655 Giovanni Ziotti wrote that ‘truly in Italy he has no equal’ as a singer, organist and composer. Giovanni Battista Volpe, another organist at San Marco, praised Cavalli’s ability to “set his texts to noble music, to sing them incomparably and to accompany them with delicate precision.”

The instrumental music on Magnificat’s Berkeley Festival program is drawn from Musiche sacre (Venice, 1656) by Monteverdi’s colleague at San Marco, Pier Francesco Cavalli. A musician of the highest caliber, Cavalli’s virtuosity as an organist was compared to Frescobaldi and in 1655 Giovanni Ziotti wrote that ‘truly in Italy he has no equal’ as a singer, organist and composer. Giovanni Battista Volpe, another organist at San Marco, praised Cavalli’s ability to “set his texts to noble music, to sing them incomparably and to accompany them with delicate precision.”