Hor che’l ciel e la terra, Francesco Petrarca

Hor che’l ciel e la terra e’l vento tace,

e le fere e gli augelli il sonno affrena,

notte il carro stellato in giro mena,

e nel suo letto il mar senz’onda giace.Veglio, penso, ardo, piango; e chi mi sfacesempre m’è innanzi per mia dolce pena;

guerra è’l mio stato, d’ira et di duol piena,

e sol di lei pensando ho qualche pace.

Così sol d’una chiara fonte viva

move’l dolce e l’amaro ond’io mi pasco;

una man sola mi risana e punge.

E perché’l mio martir non giunga a riva,

mille volte il dì moro e mille nasco,

tanto dalla salute mia son lunge. |

Now that heaven, earth and the wind are silent

and beasts and birds are stilled by sleep,

night draws the starry chariot in its course

and in its bed the sea sleeps without waves.I awaken, I think, I burn, I weep, and she who fills me with sorrow

is ever before me to my sweet distress.

War is my state, full of wrath and grief,

and only in thinking of her do I find peace.

Thus from one clear and living fountain

flows the sweet bitterness on which I feed;

one hand alone both heals and wounds me.

And therefore my suffering can never reach shore.

a thousand times a day I die, a thousand reborn

so far am I from my salvation. |

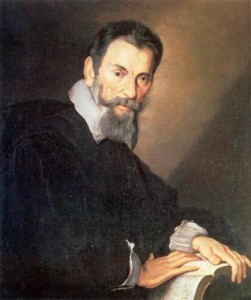

The most complex and sophisticated of Monteverdi’s large-scale madrigals from the Eighth Book, Hor che’l ciel e la terra sets, in two parts, the entirety of Petrarch’s 164th poem from the Canzoniere, a sonnet. The prima parte sets the two quatrains, and the seconda parte the two terzets. This is a poem replete with Petrarchan contrasts and oxymorons. But Petrarch’s contrasts, as described by Pietro Bembo in the Prose della volgar lingua, are brought into harmony and smoothed over the mellifluous sounds and varied, rolling rhythms of his highly refined poetic style. This is easily seen in Petrarch’s fifth and sixth lines, where the most abrupt semantic juxtapositions are couched in an elegantly structured and alliterative sentence that draws attention away from the contrasts toward their union in a highly stylized and carefully crafted poetic conception. Resemblances of rhyme, of rhythm, of line lengths and stanzaic structure, and especially resemblances of sonority all serve to overcome the semantic contrasts.

The most complex and sophisticated of Monteverdi’s large-scale madrigals from the Eighth Book, Hor che’l ciel e la terra sets, in two parts, the entirety of Petrarch’s 164th poem from the Canzoniere, a sonnet. The prima parte sets the two quatrains, and the seconda parte the two terzets. This is a poem replete with Petrarchan contrasts and oxymorons. But Petrarch’s contrasts, as described by Pietro Bembo in the Prose della volgar lingua, are brought into harmony and smoothed over the mellifluous sounds and varied, rolling rhythms of his highly refined poetic style. This is easily seen in Petrarch’s fifth and sixth lines, where the most abrupt semantic juxtapositions are couched in an elegantly structured and alliterative sentence that draws attention away from the contrasts toward their union in a highly stylized and carefully crafted poetic conception. Resemblances of rhyme, of rhythm, of line lengths and stanzaic structure, and especially resemblances of sonority all serve to overcome the semantic contrasts.

Contrasts in Petrarch’s sonnet occur on several levels. First there are the obvious, immediate contrasts between successive words or concepts in the second quatrain. “Dolce pena” at the end of the 6th line is an oxymoron; “Guerra” (war) and “pace” (peace) are contrasted in the 7th and 8th lines. In the first terzet, “dolce” (sweetness) and “amaro” (bitterness) are contrasted in the middle line, while the final line opposes “risana” (heals) with “punge” (wounds). In the middle line of the final terzet “moro” (I die) is contrasted with “nasco” (I am born).

On a larger structural level there is significant contrast between the first quatrain and the second. The first quatrain unites in silence and motionless a series of natural elements and living creatures. Even the rocking rhythm of all four lines is reminiscent of a lullaby. This quatrain is a depiction of nature at rest.

The second quatrain, in which the speaker awakes, contrasts the speaker’s individual experience with that of quiet nature. This quatrain too begins with a series, but rather than different elements being united in a smooth, rocking rhythm, “Veglio, penso, ardo, piango” are an abrupt series of wholly unrelated activities characterized by both qualitative and quantitative accents on the first syllable of each two-syllable word. The beginning of this line is an effective characterization of the intense psychological state and confusion with which one often abruptly awakens in the middle of the night. This startled series is then followed by a rational attempt to explain the psychological state: “she who undoes me is always before me for my sweet pain,” though the rationality of the thought is undermined not only by the affective oxymoron at the end, but by the seeming contradiction between the notion of the woman who undoes the sleeper also being the source of the sweet pain. The next sentence compounds the emotional contradiction. The speaker’s state is now warlike, full of anger and sorrow, but in the next line, “and only thinking of her do I have some peace,” the cause of the warlike state of mind turns out to be the only source of tranquility. In this quatrain emotional contradictions and confusions are articulated in utter contrast to the stability and tranquility of nature as described in the opening quatrain.

The sestet creates yet another contrast. The description and experience of the octet are now given additional meaning through the metaphor of the “clear, living fountain.” The fountain is the source of nourishment whence the speaker drinks both sweetness and bitterness, and the hand of the beloved, like the fountain, both heals and wounds. There is a cross-reference here to a previous canzona of Petrarch’s where two fountains of the Fortunate Isles are described: “who drinks from the one, dies laughing, and who from the other, escapes.” (Poem 135, lines 78-79)

In Hor che’l ciel, the speaker is like the waters of the fountain in that his martyrdom doesn’t reach its end so that a thousand times a day he dies and is reborn as the waters are recycled through the fountain. This is how far he is from regaining his mental health, which could only come about through resolving the emotional contradictions engendered by his lady. The sestet brings nature into relationship with the speaker; the two had been completely separate in the octet. Through the metaphor of the fountain, the speaker and nature are reunited, but this is an active, seething nature, not the sleeping nature of the opening quatrain. As a consequence, the thought is left open and unresolved at the end, as if the distance from his health must remain permanent for the speaker.

How does Monteverdi deal with this text taxonomically and iconographically? Quite clearly in separate sections focusing on specific categories of affect. The opening, which sets the entire first quatrain, consists of static chords, organized rhythmically around the rhythms of the text, although the concluding trochees of terra, tace, affrena, mena and giace are all set as spondees rather than trochees, thereby increasing even further the sense of stasis. The only pitch motion in this entire section is a slow moving I-V-I-VI-V-I chord progression, which is perhaps stimulated by the phrase “in giro mena” (leads in a circle) in the third line. It is probably no accident that the first return to the tonic chord occurs precisely with this phrase. The homogeneous opening section of the piece is thus a single icon for the tranquility described in the first quatrain of Petrarch’s sonnet.

Petrarch’s second quatrain, as we have seen, not only contrasts with the first but is also less internally unified. This leads Monteverdi in the first two lines to invent three musical metaphors in the Renaissance sense, the first interpreting the sudden awakening, the second the single word piango, and the third the rest of the sentence. But Monteverdi’s treatment of these metaphors is informed by his iconographic structural sensibilities. Each is treated as a structural device in a sophisticated interaction among the individual metaphors to create a larger structural metaphor for the confused, contradictory state expressed by the speaker. Here we have aesthetic aspects of the Renaissance madrigal serving to enrich the structural possibilities of the concertato style.

The second quatrain begins with a graphic representation of the startling awakening of the sleeper, but leading immediately to a typically Renaissance metaphor for piango (I weep) in suspended figures of falling half- or whole- steps. In contrast to the opening section, each word is now on a new chord and at a higher pitch level than the last. The continuation of the thought with e chi mi sface is cast in a descending lament in two voices in parallel thirds, the descent an obvious icon for depressed emotional states. But already Monteverdi is at work dealing with the psychological contrasts and contradictions in these two lines by superimposing a restatement of veglio, penso, ardo, piango over the completion of the thought. The restatement proceeds with wider gaps between veglio, penso, ardo and piango, thereby giving them the effect of a psychological background to the more immediate thought about the beloved who undoes the speaker. And Monteverdi artfully times these background superimpositions so that the final one, piango, occurs simultaneously with the final word of the second line, pena.

Monteverdi has by now not only created three musical metaphors, but has begun to use them in a structural fashion to expand the section as well as create the psychological connection between the sudden awakening and the cause of that awakening. Having used the original metaphors in this way, he continues to repeat and exploit them structurally, in varied form and through gradually increasing textures until all six voices are involved. This allows him to bring the section to a close, based on a structural dynamic of varied repetition in increasingly thicker textures, a structural dynamic we find over and over again in his large-scale concertato works. This process has evolved his original three metaphors into icons by the end of the section. By that time their significance has become musical-structural rather than localized and passing. They have achieved the sense of permanence and reusability characteristic of icons.

The next two lines of the quatrain contrast guerra (war) with pace (peace). As we would expect, guerra is represented by the concertato style. The final line, E sol di lei pensando ò qualche pace, is contrasted to the previous one by a homophonic and homorhythmic style in slow tempo, an obvious icon for pace. Moreover, Monteverdi drops out the lower two voices, since the thought is focused on the feminine lei, and as the state of peace is described, the harmony turns toward a cadence on B major, since peace is a decided shift of mental state for the speaker. Rather than simply quit at this point, Monteverdi once again uses structural repetition of his two icons to expand the scope of the composition and bring the prima parte to a close. This time pace cadences in E major rather than B major, and it is important to the overall structure of the madrigal that we have an inconclusive close in the dominant key at this point, leaving the way open for the sestet to bring the speaker and nature together.

The seconda parte opens with a descending figure reminiscent of e chi mi sface. This resemblance serves a structural purpose in linking the two parts of the madrigal, but also performs an affective function in relating the image of the living fountain to the beloved who undoes the speaker. One might say that the descent from e” at the beginning of the seconda parte has a musical function similar to the linking function of the word Cosí (thus) at the beginning of Petrarch’s sestet. But the most important part of the opening is the overlapping of the phrase Cosí sol d’una chiara fonte viva with Move’l dolce e l’amaro, ond’io mi pasco. The latter is set to a chromatically rising motive treated in imitation, a typical icon for situations of anguish in Monteverdi. This particular version, however, abjures dissonance almost altogether in recognition of the sweetness that is also imbibed from the fountain.

The combination of these two motives brings together in simultaneity the source of the water and its effects on him who drinks thereof. Monteverdi’s texture has gradually expanded through the imitation, reaching his typical full-textured climax, which in this case serves as the beginning of a more extended structural repetition of the chromatic motive. But there is a third line to the terzet, and Monteverdi cleverly introduces it into the texture by simply varying the descent from e and substitutes the final line Una man sola mi risana e punge.Thus when he once again reaches his textural climax, the section and the terzet can come to a close, and the passage once again has been built upon varied structural repetition.

The final terzet revolves mostly around the second line, one of the most common textual conceits of the Petrarchan 16th century and set over and over again by composers from Arcadelt through Rore to Monteverdi in multiple imitations. What started as a musical metaphor for multiplicity had early on reached the more enduring status of an icon. This line is briefly introduced by a simple, recited statement of the first line. Monteverdi’s treatment of the second line is in some respects antiphonal; only the final word, moro, set to longer notes in stepwise descent overlaps. At the end of the passage, he even makes the words nasco and moro overlap, to bring them into even closer oppositional relationship to one another than Petrarch could do in the linear medium of language. Structural repetition, transposed by a 5th, serves to enlarge the section just as in earlier portions of the piece.

Petrarch’s concluding line is somewhat separate from the rest of the sonnet in making a final statement about the poet’s situation. Monteverdi likewise sets this line apart, with a single voice in static repetition except for the word lunge, whose significance is emphasized by a long leap and even longer slow, melismatic descent. A transposed, full-textured structural repeat then serves to close out the entire madrigal, returning to the opening key. The emblematic character of this melisma is obvious in its not carrying any of the emotional weight of Petrarch’s final line.

Now that we have seen how Monteverdi has treated this text, both taxonomically and iconically, let us go back and compare what Petrarch has accomplished with his poem and Monteverdi with his music. Petrarch has taken the anguished torment of the lover who is pulled to extremes of opposing emotions and shaped it into a highly refined, elegant form. This process of shaping and refining the emotional content brings those emotions under control, into an order and a beauty that not only allows us to grasp them in multiple dimensions, but also informs us that through cultivated art the most unbridled emotions can be at least partially tamed, conceptually understood and survived. By virtue of artistic creation, it is no longer necessary for the poet to die and be reborn a thousand times a day–he can rather conceive and cope with his problem by subjecting it the imagination and structures of art and we, his readers, can share with him both the agonies described and the poet’s insight about how to manage them in a coherent fashion.

Monteverdi has taken a somewhat different approach. His goal is first of all to identify clearly the emotions and situations described by the poet. This is his taxonomic approach. His purpose is no longer to make the listener weep and laugh with the performer as the aesthetics of early opera had demanded in accordance with the Platonic theory of the transference of affect. His purpose is to convey in music knowledge about affective states–first to identify their character, then to present them for our understanding in an appropriate musical garb. This knowledge is principally of separate affects, but in both the prima parte and the seconda parte there are passages where the combination of separate ideas creates a more complicated psychological affect, which is also clearly conveyed musically. Monteverdi’s approach is more empirical than passionate, more interested in conveying concepts of emotion than in inducing emotion. The opening segment is not so much about the silence of nature as described by Petrarch, but rather about the nature of tranquility in general. The concitato section is not so much about the poet’s warlike state in this particular instance as it is about the general character of warlike agitation.

This is a more objective view than in his Mantuan works and is fully consonant with the efforts of contemporary thinkers to understand their world in more objective terms, the basis of the new empirical science of the 17th century. If we note that Monteverdi’s conclusion doesn’t sum up the significance of the poem the way that Petrarch’s final line does, that is because the significance of his musical setting cannot be summarized in a single musical statement. The significance of his setting is in the accumulation of separate and combined affects he has strung together in a sectionalized manner. Knowledge of emotion is presented by accumulation rather than by integration, and what makes such a piece good or not so good depends on the interest and quality of the musical presentation of each separate affect, plus the purely musical structural aspects of the expansive work.

(Excerpted from “A Taxonomic and Affective Analysis of Monteverdi’s ‘Hor che ’l ciel e la terra’,” Music Analysis 12 (1993): 169–95.)

Every musician searches for masterpieces to bring to the stage. For two decades, Magnificat has been in pursuit of such creations to please Bay Area audiences. Luckily, it has narrowed its focus to the 17th century, a time bursting with dynamic composers and emotional works. “It’s a tribute to the audience in the Bay Area that a group could focus on repertoire from the 17th century and be successful and have a following,” explains Artistic Director Warren Stewart. “That’s a joint effort between Magnificat and the audience.” Stewart, an accomplished cellist, has dedicated the last 20 years of his career to early music. His love of Baroque music is evident in the dynamic programming presented by the group each season. “It’s a fascinating time and period of music. Lots of things were changing, new rules were being written, and new kinds of music were being invented. I think it’s really fascinating to have the opportunity to explore that remarkable music and share it with the audience.“

Every musician searches for masterpieces to bring to the stage. For two decades, Magnificat has been in pursuit of such creations to please Bay Area audiences. Luckily, it has narrowed its focus to the 17th century, a time bursting with dynamic composers and emotional works. “It’s a tribute to the audience in the Bay Area that a group could focus on repertoire from the 17th century and be successful and have a following,” explains Artistic Director Warren Stewart. “That’s a joint effort between Magnificat and the audience.” Stewart, an accomplished cellist, has dedicated the last 20 years of his career to early music. His love of Baroque music is evident in the dynamic programming presented by the group each season. “It’s a fascinating time and period of music. Lots of things were changing, new rules were being written, and new kinds of music were being invented. I think it’s really fascinating to have the opportunity to explore that remarkable music and share it with the audience.“

![Ferdinand_III[1]](https://blog.magnificatbaroque.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/Ferdinand_III1-287x300.jpg)