Anguissola’s Novel Self Portrait

“I bring to your attention the miracles of a Cremonese woman called Sofonisba, who has astonished every prince and wise man in all of Europe by means of her paintings, which are all portraits, so like life they seem to conform to nature itself. Many valiant professionals have judged her to have a brush taken from the hand of the divine Titian himself; and now she is deeply appreciated by Philip King of Spain and his wife who lavish the greatest honors on the artist.”

Gian Paolo Lomazzo (Libro de Sogni, 1564) describing the genius of Sofonisba Anguisola in the context of an imagined conversation between Leonardo da Vinci, representing modern painting, and Phidias, the artist from Antiquity.

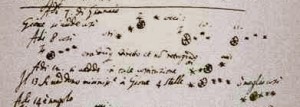

The image we’ve chosen to represent the upcoming Magnificat program featuring music by four women from the 17th century was painted by the extraordinary Sofonisba Anguissola in 1550. An exceptional work that captures the place of women in late Renaissance, the painting is both a self portrait, a portrait of her master teacher, and a compelling allegory of women as defined by men of the period. It aptly symbolizes the barriers to artistic expression faced by women and the fruits of the individual struggle in the face of those barriers.

Anguissola was born in Cremona around 1532, the oldest of seven children, six of whom were daughters. Her father, Amilcare Anguissola, was a member of the Genoese minor nobility and her mother, Bianca Ponzone, was also of an affluent family of noble background. At fourteen, Anguissola started studying with Bernardino Campi, at the Lombard school and later on under Bernardino Gatti. It is clear that her privileged status as a noble woman were a contributing factor to the fact that she had been given an opportunity to become an artist. Read more at Suite101

Although Sofonisba enjoyed much more encouragement and support than the average woman of her day, her social class did not allow her to transcend the constraints of her sex. Without the possibility of studying anatomy or drawing from life (it was considered unacceptable for a lady to view nudes), she could not undertake the complex multi-figure compositions required for large-scale religious or history paintings. Instead, Anguissola created wry and witty portraits of family members and acquaintances.

“Sofonisba’s painting of her teacher, painting her portrait – a story within a story – demonstrates how she negotiated her male-dominated world. Anguissola’s gaze rivets the viewer of the painting, forcing consideration of what appears to be the inscribing of male authority on the body of the female. Campi’s gaze complicates matters, however, since as he paints he, too, looks out of the painting toward what the picture indicates must be his subject, Anguissola. Thus the viewer in front of the painting plays a double role: that of the subject of the painting within the painting, namely Anguissola herself, and of an engaged viewer – watched by both Campi and Anguissola – made complicit in Anguissola’s destabilizing of contemporary social norms.” (Read more at wga.hu)

Isabella Leonarda

Isabella Leonarda