A Little Work in the Representative Style – Monteverdi’s Combattimento

Magnificat will perform Monteverdi’s Il Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda along with other madrigals by Monteverdi and instrumental music by Dario Castello and Biagio Marini on the weekend of September 25-27 2015. The Testo role will be sung by Aaron Sheehan, Clorinda by Christine Brandes and Tancredi by Andrew Rader. Tickets are available at magnificatbaroque.tix.com, by phone at (800) 595-4849. To order by mail download this order form (pdf).

Claudio Monteverdi’s celebrated Il Combattimento di Tancredi and Clorinda, was first performed in Venice during Carnival of 1624 at the palace of one of the composer’s patrons, though it was only published some fourteen years later in the Eighth Book of Madrigals. In the introductory notes, Monteverdi describes how the piece was first performed “as an evening entertainment, in the presence of all the nobility, who were so moved by the emotion of compassion that they almost shed tears, and who applauded, since it was a genre of vocal music never seen nor heard.” Monteverdi subtitled the Eighth Book Madrigali guerrieri et amorosi con alcuni opuscoli in genere rappresentativo (“Madrigals of war and love with some pieces in the theatrical style”), and the texts repeatedly expound the interlocking themes of love and war– the warrior as lover, the lover as warrior and the war between the sexes.

The relationship between love and war had been a common Italian poetic conceit ever since the time of Petrarch in the 14th century, and had been given additional impetus by its prominence in Torquato Tasso’s late 16th century epic poem, Gerusalemme Liberata (“Jerusalem Liberated”). This enormously influential work dealt with the first crusade and treated in a dramatic and scenographic manner not only battles between Christian and Muslim knights, but also their love affairs, including the love between the Christian knight Tancrid and the Muslim woman Clorinda, who, disguised as a knight in full armor, fiercely fought for her side.

Monteverdi affixed an explanatory preface to the Eighth Book, a theoretically important, though sometimes confusing description of what he had tried to achieve in this music. Monteverdi explains how he “took the divine Tasso, as a poet who expresses with the greatest propriety and naturalness the qualities which he wishes to describe, and selected his description of the combat of Tancredi and Clorinda as an opportunity of describing in music contrary passions, namely, warfare and entreaty and death.” The composer describes three emotional levels, which he also calls styles. Two of these, the “soft” style (stile molle) for languishing and sorrowful emotions, and the “tempered” style (stile temperato) for emotionally neutral recitations, he says had long been in use. But the third style, the “agitated” style, (stile concitato), Monteverdi claims to have invented himself.

The musical depiction of this style consists of very rapid reiterations of the same pitch on string instruments, like a modern measured tremolo, and equally rapid reiterations of the supporting chord in the harpsichord or other continuo instrument. Such repeated notes and repeated chords had, in fact, been frequently used in compositions depicting battles for nearly a century, but for Monteverdi the stile concitato meant more than merely a musical metaphor for the rapid physical activity of fighting. It was also a specific emotional style–a musical means for interpreting the emotional agitation of the protagonists and conveying that agitation to the audience. The stile concitato, therefore, serves both a pictorial and a psychological function in Monteverdi’s music.

Monteverdi’s music is written for a narrator who sets the scene for us in recitative, (principally the stile temperato), comments on the progress of the battle as it takes place, and reflects on the inner thoughts of the two characters. The swordfight between the active participants, Tancrid and Clorinda, is the arena for the new stile concitato. The battle takes place during the obscuring night, and both protagonists are fully dressed in armor so that they do not recognize one another. They fight fiercely, with increasing anger on Tancrid’s part as Clorinda gradually loses ground but remains defiant. When she finally lies mortally wounded, she asks Tancrid for baptism, and as he bends over her and lifts her visor to pour the cleansing water over her face, he recognizes with horror that he has killed his beloved. Triumph has turned to tragedy. As dawn breaks, Clorinda dies in Tancrid’s arms, but in peace because of her religious conversion. It is a scene of grand theatrical pathos in which Monteverdi employs the stile molle to great effect.

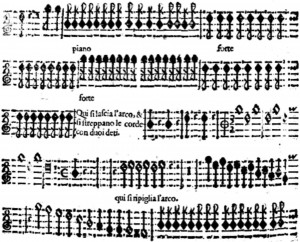

In the past Il Combattimento was sometimes cited as including the first explicit instructions for pizzicato, a distinction actually held by Thomas Hume, who called for the technique in his collection of viola da gamba music Captain Humes Poeticall Musicke, published in 1607. In the image to the right from the first violin part of Il Combattimento, Monteverdi calls on the player to “pluck the string with two fingers” and later to once again “take up the bow.” Of course the fact that the technique of plucking the strings preceded its explicit designation is obvious and it is likely that Monteverdi, who began his professional career as a string player, and other violinists employed the technique long before it appeared in print.

Magnificat has programmed Il Combattimento twice before. In 1991, we performed the work with Kenn Chester (Testo), Susan Rode Morris (Clorinda) and Boyd Jarrell (Tandredi) on the San Francisco Early Music Society and San Jose Chamber Music Society concert series. In 2000 the work was featured on our own series with Kenn Chester again in the Testo role, Jennifer Ellis Kampani as Clorinda and Peter Becker as Tancredi. Portions of this article are drawn from program notes by Jeffrey Kurtzman from our 2000 production.