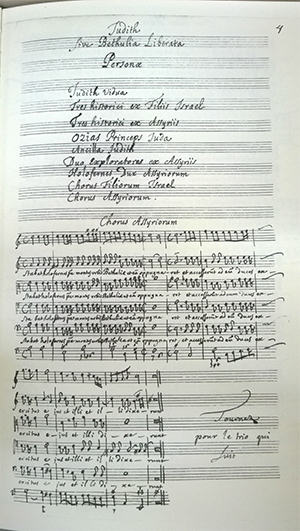

Charpentier’s Oratorio Judith, ou Béthulie libérée

Judith, ou Béthulie libérée, (Judith, or Bethulia Liberated) was the first histoire sacrée composed by Charpentier, and is his longest. The text is adapted from the Book of Judith, 7-14 of the Old Testament. Judith devotes a very large role to the narrator or narrators, and thus to declamatory ensembles. In order to diversify the narration, Charpentier assigns the part of the historicus in alternation to soloists, vocal trios, and choruses, with the latter two shifting between homophonic texture and imitative counterpoint. Within a single section of recitative, a wholly declaimed vocal line can give way to more lyrical arioso, as in the long dialogue between Holofernes and Judith. The airs are all in rondo form (ABA or ABACA). Since they essentially fulfill the role of narrator, choruses are not very elaborate and remain homophonic in style.

Judith, ou Béthulie libérée, (Judith, or Bethulia Liberated) was the first histoire sacrée composed by Charpentier, and is his longest. The text is adapted from the Book of Judith, 7-14 of the Old Testament. Judith devotes a very large role to the narrator or narrators, and thus to declamatory ensembles. In order to diversify the narration, Charpentier assigns the part of the historicus in alternation to soloists, vocal trios, and choruses, with the latter two shifting between homophonic texture and imitative counterpoint. Within a single section of recitative, a wholly declaimed vocal line can give way to more lyrical arioso, as in the long dialogue between Holofernes and Judith. The airs are all in rondo form (ABA or ABACA). Since they essentially fulfill the role of narrator, choruses are not very elaborate and remain homophonic in style.

Part 1 is set at the foot of the mountains near the city of Bethulia. The Chorus of Assyrians tell how Holofernes and his army are preparing to attack the city. In a sung trio, three of his commanders tell how the Israelites are counting on the steep cliffs to protect them, and they recommend cutting off their water supply by placing a guard at their well. An Assyrian recounts how this plan pleased Holofernes, and for the next twenty days the Israelites went without water. The scene changes to the camp of the thirsty Israelites and an Israeli relates how three of them went to ask their leader Ozias to surrender to Holofernes. The trio of Israelistes say that it is clear that God had delivered them into his hands and that it would be better to die swiftly by the sword than slowly by thirst, and, in a chorus of startling harmonic richness, the Israelites bewail how they have sinned and acted unjustly and that this is their well-deserved punishment. They grow weary and then Ozias arose and in a dancelike solo air he tells his people to take heart and wait five more days for mercy from God; if no aid arrives by then, they will surrender to Holofernes.

A trio of Israelistes then relate how Judith, a daring and beautiful widow, arose and addressed the people. In solo arioso, Judith tells them that they should not set a time limit for God to deliver them from their foreign conquerers and in an aria advises them to adopt an attitude of humility that may become for the Israelites a thing of glory. Judith then reveals to Ozias that she has a plan to save her people. Part 1 concludes with a series of set-pieces. First, a glorious concertante Chorus of Israelites sends Esther on her mission with their best wishes. Then a solo historicus explains that the following night, Judith put on haircloth, spread ashes in her hair, and prayed to the Lord. Judith’s sung prayer, interspersed with ritornelli for flutes and continuo, is the musical high point of Part 1. Here she reveals her plan to use her beauty to entrap Holofernes with his eyes and then cut off his head with his own sword.

After her prayer, Judith bathed, anointed herself with myrrh, plaited her hair, put on garments of gladness, and left the city with her handmaiden. An evocative instrumental number entitled “The Night” concludes Part 1, and requires further explanation from Pierre Le Moyne’s article on Judith in his Galerie des femmes fortes (Paris: Sommaville, 1647, pp. 39-44):

The Angel of Israel, has come in person to defend the frontier of his nation. He has created shadows where there is something of the shadows that he once created in Egypt. And by his command, Night has come early, contributing its silence and its darkness to the great action he is preparing. But this darkness is only for the enemies of God’s people; and this intelligent Night is discrete, as was the night in Egypt, and is very capable of singling out the faithful and distinguishing between individuals. What is fog and shadows for others will be light for us. And even if there is only the brightness of these luminous spirits, added to the glow of Judith’s zeal and eyes, which seem to set fire to all the gems of this superb tent, that would be enough to see, from here, the Tragedy that is beginning in the tent of Holofernes.

In Part 2, we learn from the handmaiden’s narration that she and Judith descended the mountain at sunrise and were met by two Assyrian watchmen. The watchmen question her and Judith responds by promising information on the Israelites and they escort her to their prince The Assyrian Chorus relates that she was taken to Holofernes’s tent and that he was immediately attracted by the her beauty and caught “in the net of his own eyes” depicted by interweaving melodic lines. Esther falls down to worship him but Holofernes commands her to rise. In a solo air, Holofernes tells Judith not to be afraid, and asks her why she deserted her people. Judith tells him that the sins of the Israelites have angered their God, who has abandoned them, and she offers to take Holofernes with her to Bethulia. Holofernes tells her that as her God has done well, her God shall become his God; and so Holofernes promises Judith riches and invites her into his tent to partake of wine. Judith responds coyly “Who am I, that I should oppose the will of my Lord?”

In Part 2, we learn from the handmaiden’s narration that she and Judith descended the mountain at sunrise and were met by two Assyrian watchmen. The watchmen question her and Judith responds by promising information on the Israelites and they escort her to their prince The Assyrian Chorus relates that she was taken to Holofernes’s tent and that he was immediately attracted by the her beauty and caught “in the net of his own eyes” depicted by interweaving melodic lines. Esther falls down to worship him but Holofernes commands her to rise. In a solo air, Holofernes tells Judith not to be afraid, and asks her why she deserted her people. Judith tells him that the sins of the Israelites have angered their God, who has abandoned them, and she offers to take Holofernes with her to Bethulia. Holofernes tells her that as her God has done well, her God shall become his God; and so Holofernes promises Judith riches and invites her into his tent to partake of wine. Judith responds coyly “Who am I, that I should oppose the will of my Lord?”

Judith’s coy behavior here might seem inconsistent with her virtuous and devout character. However, Pierre LeMoyne sheds light on her seduction of Holofernes by explaining that, essentially, Judith temporarily adopts what might in our day be described as a split personality:

But this is not the Judith that Virtue, Zeal, and the angles have brought here. This is a Judith fashioned by a deluding dream (un Songe imposteur), which has made a coquette of the heroine: and this coquettish and false Judith will soon be struck down by the true and modest one. The sword you see in her hand will deliver justice to this imposter-dream: and all of these vain images will be drowned in the blood of the dreamer [i.e., Holofernes], and will fall with his head.

Judith entered the tent with Holofernes, his servants withdrew and the prince so enjoyed her company that he drank too much wine. Judith’s handmaiden continues the narration, telling that while Holofernes lay on his bed in a drunken stupor, Judith said a prayer for the Lord’s strength and decapitated him with his own sword. Stuffing the severed head into her maid’s sack, Judith and her servant quietly passed through the Assyrian camp, wound through the valley, and finally arrived at the city gates. In a solo air, Judith asks the watchmen to open the gates for “God is with us who hath shown his power in Israel.” The Chorus of Israelites relate how all the population “from the least to the greatest” rushed out to meet her and gathered round her with lighted torches; and she ascended to a higher place, she commanded silence from the people. In a solo air, Judith praises the Lord, uncovers the head of Holofernes “which the Lord struck off through the hand of a woman,” and that she has returned to them without any stain of sin. Judith then exhorts her countrymen to sing a canticle of praise to the Lord. This final blessing is a magnificent concertante set piece inspired by a reading of the feast of the Assumption—where Judith is presented as a prefiguration of the Virgin Mary.