Francesco Cavalli’s Messa Concertata

“Francesco Cavalli truly has no peers in Italy, in the perfection of his singing, in the worth of his organ playing, and in his exceptional musical compositions, of which those in print bear witness to his merit.”

“Francesco Cavalli truly has no peers in Italy, in the perfection of his singing, in the worth of his organ playing, and in his exceptional musical compositions, of which those in print bear witness to his merit.”

The Venetian chronicler Ziotti’s effusive praise of Cavalli, published 1655, reflects the universal acclaim the composer enjoyed at the height of his long and robust musical career. The son of the organist and composer Giovanni Battista Caletti, Cavalli was born in the small but prosperous town of Crema near Milan but still within the borders of the Venetian Republic in 1602. At the age of 13 Francesco’s exceptional voice and prodigious musical talents drew the attention of Frederico Cavalli, the Venetian governor in Crema. Cavalli offered to take the boy to Venice where he could benefit from exposure to the rich musical life there – a proposal only reluctantly accepted by the boy’s father.

Within months of his arrival, Cavalli was engaged as a singer at the Basilica of San Marco under its newly appointed maestro Claudio Monteverdi, who was in the midst of restoring the musical institution of the Basilica to its former heights under Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli. For the remaining six decades of his life, Cavalli would remain in the employ of the Basilica, where he would work with the most esteemed musicians of his age. Additionally, his status as musician in the Cappella Marciana, together with his undisputed gifts as a singer, organist and composer, insured a steady flow of outside work at the many well-endowed churches, scuole grandi and in the noble palaces of The Most Serene Republic.

While musically and professionally the situation at San Marco could hardly be matched, Cavalli’s early separation from his family and the pressure of professional responsibilities at a young age had an impact on his first years at San Marco. He lived first with Federico Cavalli, whose surname he later adopted, but appears to have moved frequently, most often living by various other wealthy patrons among the Venetian elite, some of whom bailed him out of gambling debts and otherwise supported the brilliant, but occasionally reckless young prodigy.

Like all Venetians, Cavalli’s life was profoundly impacted by the “The Great Plague of Milan”, which arrived in the winter of 1630. Historians have suggested that a strain of bubonic plague was brought to Lombardy the previous year by foreign soldiers engaged in the catastrophic siege of Mantua and gradually moved from city to city. Over 80,000 Venetians perished in 1630 and over the next two years the plague would claim over a quarter million lives as it spread across northern Italy.

At the height of the plague, Cavalli was married to Maria Sosomeno, the recent widow of wealthy patrician Alvise Schiavina. The marriage proved to be as successful and affectionate as it was financially beneficial and Cavalli readily adapted to his new role of landowning businessman. In addition to relieving him of the financial anxieties characteristic of the life of a professional musician, his new prosperity, coupled with his outstanding musical talent, positioned him perfectly to get in on the ground floor of one of the most momentous developments in music history: the advent of public opera.

In 1637 a small troupe of singers and instrumentalists had staged Andromeda, an opera by Francesco Mannelli, at the Teatro San Cassiano. The newly conceived notion of entirely sung drama, until then the exclusive privilege of the nobility in the courts of Mantua, Florence and Rome, proved sensationally popular among the relatively broad spectrum of Venetian society that could afford the price of admission. Mass media music was born.

Cavalli was quick to recognize opera’s commercial potential and joined with a group of investors and artistic collaborators to emulate the success of Andromeda and within a year began presenting regular operatic production at San Cassaino, beginning with his own Le Nozze di Teti e di Peleo. Over the next three decades, in the roles not only of performer, director and composer, but also venture capitalist and impresario, Cavalli would be the dominant figure in – and most powerful influence on – the first generation of opera as the musical theater establishment we know today. Between 1639 and 1669, Cavalli wrote 32 works for the stage. At the peak of his career he received the exceptional honor of a commission to write and stage an opera for the occasion of the marriage of the Dauphin, Louis (later to be Sun King) to the Spanish Hapsburg Maria Theresa in 1659.

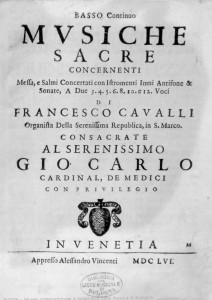

Throughout this time, Cavalli continued in the service of the Cappella Marciana first as a singer and later as organist. As early as 1625, a Song of Songs setting by Cavalli was included in a sacred anthology along with works by Monteverdi, Grandi and other musical luminaries. In 1650 he edited a posthumous collection of Monteverdi’s sacred music in which he included his own six-voice Magnificat. But it was not until 1656, at the height of his operatic fame, that he published his first collection of sacred music, Musiche Sacre, from which the eight voice concertato setting of the Mass ordinary on our program was drawn.

Throughout this time, Cavalli continued in the service of the Cappella Marciana first as a singer and later as organist. As early as 1625, a Song of Songs setting by Cavalli was included in a sacred anthology along with works by Monteverdi, Grandi and other musical luminaries. In 1650 he edited a posthumous collection of Monteverdi’s sacred music in which he included his own six-voice Magnificat. But it was not until 1656, at the height of his operatic fame, that he published his first collection of sacred music, Musiche Sacre, from which the eight voice concertato setting of the Mass ordinary on our program was drawn.

Dedicated to Cardinal Giovanni Carlo de’ Medici, to whom Cavalli’s opera Ipermestra had been dedicated two years earlier, Musiche sacre is monumental even in the context of previous magisterial publications by Monteverdi, Rovetta, Rigatti and other Venetian masters. With no fewer than 28 compositions, the volume included, in addition to the Mass, grand-scale settings of several Vespers psalms, intimate hymns and motets and a set of six ensemble sonatas. The Mass setting exudes a confident brilliance and solemn grandeur well suited to the celebration of the Holy Nativity, though it was most likely composed initially to mark the occasion of a 1644 peace treaty between Rome and Parma.

The Mass also displays the innovative theatrical styles that Cavalli had explored and in his music for the stage, and he effortless incorporates the dramatic gestures and sharply contrasting textures found in his operas into his concertato settings o the liturgical text. There are even passages of secco recitative, the most idiomatic feature of early opera. Perhaps the most striking echo of Cavalli’s operatic style is his use of sequences and transpositions to extend the melodic structure and the harmonic clarity found in his articulation of the musical architecture.

After his return from France in 1662, Cavalli again wrote for the Venetian theater, but the financial rewards of his Royal commission and changing operatic fashions resulted in a more relaxed compositional pace. In 1668 Cavalli was unanimously chosen by the Procurators to succeed Giovanni Rovetta as maestro di cappella, a position he held until his death in 1676. Cavalli would publish one more collection of sacred music in 1675: a somewhat austere set of psalms and Magnificats required for the “Cinque Laudate” feasts unique to the liturgy of San Marco. With Cavalli’s death, Venice lost one of the musical giants of the seventeenth century and one the last of the direct links with Monteverdi.