Monteverdi: Vespro della Beata Vergine (1610)

- Monteverdi: Vespro della Beata Vergine (1610)

- Monteverdi’s Work Sample

- Monteverdi’s Successful Audition

- Monteverdi and Musical Coherence

- “With various and diverse manners of invention and harmony”

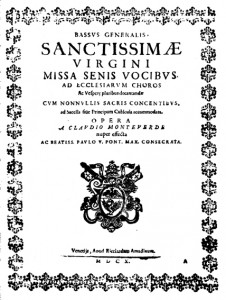

Claudio Monteverdi’s very earliest, youthful publications were sacred, devotional music: a set of Sacrae Cantiunculae published in 1582 when he was only fifteen, and a collection of Madrigali spirituali, issued in 1583. But once he became employed at the ducal court of Vincenzo Gonzaga in Mantua, probably in late 1590 or early 1591, his published works until 1610 consisted entirely of secular music: madrigals, scherzi musicali, and the opera Orfeo. On September 1, 1610, however, he published a very large and elaborate collection of sacred music comprising a six-voice Missa in illo tempore in a conservative contrapuntal style and the brilliant and variegated Vespro della Beata Vergine employing every modern compositional technique imaginable in the early 17th century.

The Mantuan secular works, including the unpublished but famous opera Arianna, were all connected to particular events and entertainments at court. However, we know from letters and other documents that the Missa in illo tempore was not composed for any specific occasion in Mantua, nor do we have any evidence that the Vespro della Beata Vergine was either. We do know that at least from 1603, Monteverdi was responsible for a great deal of sacred music associated with the court, but until 1610 none of it was published nor does any survive in manuscript. Why would he publish such a large sacred collection in 1610?

From Monteverdi’s letters and a letter of his father, we know that the composer was sick and exhausted by the summer of 1608 from a very strenuous period of work in Mantua. In less than a decade his reputation as one of the most prominent composers in Italy had been established through the publication of his Fourth and Fifth books of madrigals (1603 and 1605), his first book of Scherzi musicali (1607), the opera Orfeo (1607, first published in 1609), several reprints of his First, Second and Third books of madrigals in 1600, 1604 and 1607, and reprints of his Fourth and Fifth books in 1605-1608. Moreover, the opera Arianna (1608) was such a success that word about it quickly spread far and wide. But Monteverdi had also been publicly attacked for his modern style of composition. In 1600 the theorist Giovanni Maria Artusi, a champion of 16th-century counterpoint, had published a treatise on the imperfections of modern music in which he singled out several madrigals by Monteverdi, chastising their violations of the rules of traditional counterpoint and modal coherence. A public polemic between Artusi and Monteverdi ensued lasting eight years, and the composer’s pride was clearly hurt by this assault. He even promised a treatise explaining the rationale of modern music, though it never materialized.

In addition to responding to this attack, Monteverdi was under constant pressure to compose in Mantua. This pressure reached its apex in 1608 with preparations for the marriage of the duke’s son Francesco, which was celebrated in late May and early June of that year with the opera Arianna and much other music, some of it also composed by Monteverdi. It had been a bad year—his wife Claudia, herself a court singer, had died in September 1607, causing the widowed composer to lose her income. Most of Arianna was feverishly written in the last two months of that year. In early March 1608, Caterina Martinelli, a young singer trained by Monteverdi and living in his household who was rehearsing the demanding lead in Arianna, suddenly died from smallpox, causing postponement of the production and a hasty search for another performer who could quickly learn the role. Added to these travails were the strains of preparing the score of Orfeo for publication, Monteverdi’s continual difficulties in collecting his salary from the court treasurer and the humid, unhealthful Mantuan climate resulting from its location in the midst of swampy marshes surrounding the Mincio river. After the wedding festivities, Monteverdi retired to his father’s house in Cremona, distraught and ill. That fall he sought dismissal from the duke’s service, or at least to have his work confined to sacred music only. However, the duke refused, and by January 1609 he was back in Mantua, desperate to find a new job, especially as maestro di cappella in a major church where the duties were fixed and predictable according to the liturgical calendar. The problem was that he had not published any sacred music for 27 years and no liturgical music at all.

These circumstances seem the obvious impetus for his composing in the first half of 1610 the Missa in illo tempore, a contrapuntal tour-de-force that answered the criticisms of Artusi about his ability to write in the old style. At the same time he gathered together a number of psalms, motets, a hymn and two Magnificats, some of which had probably been written several years earlier, and some of which may have been newly composed, into a liturgically coherent collection fulfilling the needs for a Vesper service for any feast of the Blessed Virgin Mary. It is into these pieces that he poured his immense creativity in the new styles of music emerging in the late 16th and early 17th centuries to produce what to that time had been the most colorful and vocally splendid music ever written for a liturgical service. But despite their modernity, the majority of these compositions are based on the traditional Gregorian chants for the psalms, Magnificat, hymn and litany of the Virgin, generating a palpable tension between the traditional chant and the new styles of music in which it was embedded. With the Missa in illo tempore and the Vespro della Beata Vergine, Monteverdi at a stroke showed himself to be the pre-eminent Italian master of composition in all styles of sacred music, both old and new.

The 1610 publication was dedicated to Pope Paul V, and in the fall of that year Monteverdi went to Rome to present the newly minted edition personally to the Supreme Pontiff in hopes of obtaining admission for his son Francesco to the papal seminary, and probably to discreetly seek out job possibilities in Rome. He was unsuccessful on both counts and returned to Mantua by January 1611 empty-handed. In early 1612, duke Vincenzo Gonzaga, Monteverdi’s patron died and was succeeded by his own son Francesco, who had also been one of the composer’s patrons. But Francesco Gonzaga inherited a financial mess from his profligate father and in July 1612, angry at what he considered the arrogance of Claudio and his brother Giulio Cesare (also a court musician), fired both of them along with about half his musical establishment.

In July 1613, with the death of the maestro di cappella at St. Mark’s in Venice, the most important musical position in northern Italy became vacant and Monteverdi was recommended to the officials of the basilica as the most worthy candidate. They were aware of his recently published sacred music, and on August 15, 1613 he auditioned at St. Mark’s, celebrating Mass and Vespers on the feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin, quite possibly including music from his 1610 print. Four days later he was officially appointed maestro di cappella. Monteverdi served the Republic for the remainder of his life, another thirty years, well-paid, revered and recognized as the finest composer of his age.

Magnificat

Magnificat