Another Review: Francesca Caccini’s La Liberazione di Ruggiero dall’ Isola Alcina

The following thoughtful review was posted at the blog Exotic and Irrational Entertainment by “Pessimissimo”. I especially appreciate the recognition of the excellent program notes by Suzanne Cusick, who contributed tremendously to my understanding of Francesca and her “show”. The reviewer’s comments about Pulcinella are well taken, I would only point out that, the commedia figures were not only associated with Sicilian theatre, but with Italian theater in general and the performance of commedia troupes at any event like the visit of a foreign dignitary, especially during Carnival was taken for granted (and in fact mandatory for the companies enjoying the protection of the Medici). That being said, they certainly were not part of the original performance in 1625, but then neither were puppets of any sort. Thanks for such a well considered review!

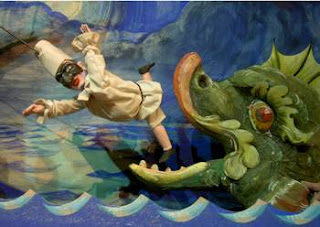

This past week in the Bay Area the Baroque vocal group Magnificat (in collaboration with the Carter Family Marionettes) performed Francesca Caccini’s La Liberazione di Ruggiero dall’ Isola d’Alcina (The Liberation of Ruggiero from Alcina’s Island, 1625) as a puppet opera. (Images from the website of Magnificat.)

This past week in the Bay Area the Baroque vocal group Magnificat (in collaboration with the Carter Family Marionettes) performed Francesca Caccini’s La Liberazione di Ruggiero dall’ Isola d’Alcina (The Liberation of Ruggiero from Alcina’s Island, 1625) as a puppet opera. (Images from the website of Magnificat.)

Francesca Caccini was a remarkable figure. According to scholar Suzanne Cusick’s informative program notes, Francesca was the daughter of the famous singer and composer Giulio Caccini (of “Amarilli, mia bella” fame). Francesca sang at age 13 in the first opera to have survived complete, Jacopo Peri and Ottavio Rinuccini’s L’Euridice (1600), to which her father also contributed music. Francesca not only had a beautiful singing voice by contemporary accounts, but was a multi-instrumentalist and later a teacher and composer as well. She wrote hundreds of songs and music for at least 17 entertainments for the Medici Court in Florence. Unfortunately most of her songs are lost, and the only one of her operas that survives in performable form is La Liberazione di Ruggiero.

Ferdinando Saracinelli’s libretto takes its story from the same portions of Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso (1532) from which Handel’s Alcina (1735) was drawn. The knight Ruggiero has been seduced by the beautiful (but evil) sorceress Alcina and is lingering with her on her enchanted island. Ruggiero doesn’t realize the danger he’s in: he’s just the latest in a series of conquests that Alcina has bewitched; his predecessors have been turned into the lush plant life that covers her island. The beautiful (but good) sorceress Melissa and Ruggiero’s betrothed, Bradamante, go to Alcina’s island to shame Ruggiero into returning to his martial (and marital) duties. As Ruggiero dons his armor and prepares to leave, Alcina at first pleads with him to stay. But when her tears fail, she vengefully uses her magic to unleash demons and fire against Ruggiero. Ruggiero’s valor and Melissa’s counter-magic triumph, however: the other enchanted knights and ladies on the island are freed, the demons are overcome and Alcina is vanquished.

Cusick’s program notes make the case that this story wasn’t chosen at random–that it functions as a partial allegory of the complex political situation in the Medici territories, which were then co-ruled by the regent Archduchess Maria Maddalena and her mother-in-law, Christine de Lorraine. I’m not completely convinced. First, along with Homer, Virgil, Ovid, and Tasso, Ariosto’s chivalric romances were part of the common currency of stories that composers and librettists could be assured that their courtly audiences would be familiar with. Additionally, if the opera is an allegory the role of Alcina is highly problematic. Unlike her portrayal in Handel’s opera a century later, her depiction in La Liberazione di Ruggiero–while initially sympathetic–turns unequivocally negative by the end of the opera. So we have a battle between a good witch (Melissa) and a bad witch (Alcina) over a man reluctant to assume his duties. If the good witch is seen as Maria Maddalena, the bad witch then becomes associated with Christine, and the reluctant knight with Ferdinando II de Medici, for whom Maria Maddalena and Christine were acting as regents. Such associations could not have been anything but highly offensive to Christine, a very powerful woman who was likely present at the first performance.

Cusick’s program notes make the case that this story wasn’t chosen at random–that it functions as a partial allegory of the complex political situation in the Medici territories, which were then co-ruled by the regent Archduchess Maria Maddalena and her mother-in-law, Christine de Lorraine. I’m not completely convinced. First, along with Homer, Virgil, Ovid, and Tasso, Ariosto’s chivalric romances were part of the common currency of stories that composers and librettists could be assured that their courtly audiences would be familiar with. Additionally, if the opera is an allegory the role of Alcina is highly problematic. Unlike her portrayal in Handel’s opera a century later, her depiction in La Liberazione di Ruggiero–while initially sympathetic–turns unequivocally negative by the end of the opera. So we have a battle between a good witch (Melissa) and a bad witch (Alcina) over a man reluctant to assume his duties. If the good witch is seen as Maria Maddalena, the bad witch then becomes associated with Christine, and the reluctant knight with Ferdinando II de Medici, for whom Maria Maddalena and Christine were acting as regents. Such associations could not have been anything but highly offensive to Christine, a very powerful woman who was likely present at the first performance.

Magnificat’s production was a pastiche of elements, many of which were deliberately anachronistic. All questions of “authenticity” dissolved, though, in the charming performances. The puppets were an ingenious solution to the problem of staging this spectacular opera, which features mermaids, sorceresses on flying dragons, singing trees, and a concluding (sea)horse ballet. There was a natural connection between the opera and the working-class Sicilian puppet theater tradition, which incorporates figures from the chivalric romances (the armored figures of Ruggiero and the rescued knight Astolfo were, we were informed, actually constructed in Sicily). The Baroque stagecraft in miniature was utterly delightful: the rolling ocean waves, flying dragons, sea monsters, magical transformations, and the highly amusing references to The Sound of Music and The Wizard of Oz were handled with captivating cleverness.

And of course, even in a puppet version the opera had a full share of Baroque gender-bending: Melissa, sung by a male countertenor, cross-dresses as Ruggiero’s former mentor Atlante in order to confront him; meanwhile, the same male countertenor voiced one of the three damigelle who were Alcina’s handmaidens.

The only element of the production that I had mixed feelings about was the puppet Pulcinella, who commented on and participated in the action intermittently throughout the opera. Pulcinella, a commedia dell’arte character associated with earthy jokes and comic misadventures, is a common figure in Sicilian puppet theater, so his presence made sense. But it’s highly unlikely that comic interludes were part of the initial performance of the opera (courtly decorum would not have permitted it). And truth be told, I found it difficult to switch between Caccini’s beautiful music and Pulcinella’s bad puns, bawdy gestures and scatological jokes.

The only element of the production that I had mixed feelings about was the puppet Pulcinella, who commented on and participated in the action intermittently throughout the opera. Pulcinella, a commedia dell’arte character associated with earthy jokes and comic misadventures, is a common figure in Sicilian puppet theater, so his presence made sense. But it’s highly unlikely that comic interludes were part of the initial performance of the opera (courtly decorum would not have permitted it). And truth be told, I found it difficult to switch between Caccini’s beautiful music and Pulcinella’s bad puns, bawdy gestures and scatological jokes.

All in all, though, the production was a brilliant success on every level–and most especially the musical. The musicians and singers of Magnificat were uniformly excellent, and Caccini’s music was simply gorgeous. I have to mention by name soprano Catherine Webster (Alcina), mezzo-soprano Jennifer Paulino (Sirena, Damigelle), alto countertenor José Lemos (Melissa/Atlante and other characters), and bass Hugh Davies (Nettuno)–their contributions in particular were superb. But every member of Magnificat and the Carter Family Marionettes should congratulate themselves on a triumph.

This review is reposted from the original posting here.